Why this question matters?

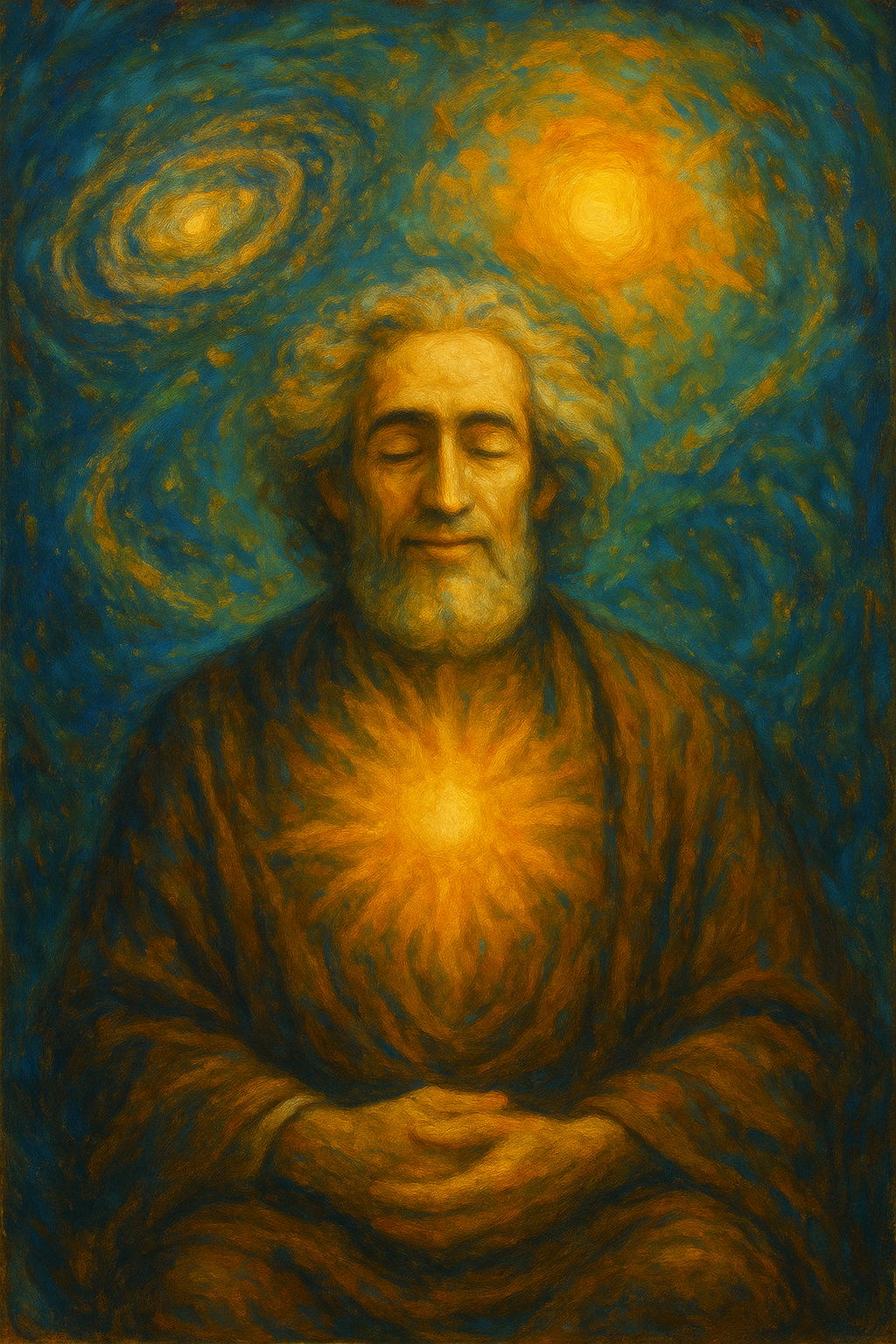

Can rigorous reason produce something like mystical peace? For thenoetik readers—who value noesis (intellect + intuition)—this is more than academic curiosity. It’s a practical question about whether a philosophical system, built on causal explanation and naturalism, can reshape experience in ways we normally call spiritual: calmness, awe, and deep connectedness. The focus keyword for this piece is ‘Spinoza cosmic joy.’ We’ll translate Spinoza’s technical claims into felt descriptions and usable practices so creatives and curious readers can test whether philosophy can become a lived, joyful method.

Compact bio & context: Spinoza in a paragraph

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin. His mature work, the Ethics (Ethica), is famously written in geometric form—definitions, axioms, propositions—aiming to show philosophically what follows from his premises. Spinoza radicalized theology and metaphysics with the formula ‘Deus sive Natura’ (God or Nature), insisting there is one infinite substance manifesting under attributes such as thought and extension. Rather than a transcendent personal deity, Spinoza’s God is immanent reality itself. The ethical upshot culminates in the concept commonly translated as the intellectual love of God (amor intellectualis Dei), which he links to blessedness (beatitudo).

Key concepts explained plainly

- Deus sive Natura (God or Nature): Spinoza’s shorthand: the infinite ground of all that exists is one substance. Nothing lies outside nature; divine reality is identical with the world. (See Ethics, Preface and Part I.)

- Conatus (striving): Every thing strives to persevere in its being. For minds, conatus is expressed as desires, aims, and the power to act—this is the psychological engine behind motivation and emotion. (Ethics, Part III.)

- The three kinds of knowledge (cognitio):

- Imaginative knowledge (opinion/imagination): fragmentary, mediated by sense and language—prone to error.

- Reason: adequate, general ideas that explain common natures; brings regularity and stability.

- Intuitive or ‘third’ knowledge (scientia intuitiva): direct grasp of things as expressions of the whole—immediate, holistic insight into things’ relations to God/Nature. Spinoza treats this as the highest form of knowledge (Ethics, Part II and V).

- Affects (affectus): The mind’s modifications—joy, sadness, desire—rooted in the body’s states. Spinoza analyzes how inadequate ideas and passive affects diminish power, while adequate ideas increase our capacity to act.

- Intellectual love of God (amor intellectualis Dei): A rational, yet affective, loving joy that arises when the mind understands its place in the whole. For Spinoza, this love is not sentimental devotion but a lasting beatitude grounded in knowledge (Ethics, Part V).

Mechanism: From knowledge to joy — stepwise

Spinoza gives a clear—if terse—pathway from thinking to beatitude. Here’s the pathway, step-by-step and in accessible language:

- Explain the world: acquire adequate ideas. Replace confused, fragmentary interpretations (imagination) with clear, general explanations (reason). Adequate ideas track real causal relations and free us from error.

- Increase active power: when the mind has adequate ideas, affects shift from passivity (being acted upon) to activity (acting from understanding). This changes the balance of power in our conatus: we become more capable of flourishing.

- Grasp the whole: through the third kind of knowledge (intuitive knowledge), the mind sees particular things as necessary expressions of the one substance. This is not mystical haze but a sudden comprehension of how things are interconnected.

- Intellectual love and beatitude: that comprehension yields an enduring joy—amor intellectualis Dei—because the mind now rejoices in the necessity and harmony of things. Spinoza writes that ‘the more we understand, the more we love’ (see Ethics, Part V). The joy is cognitive and affective at once: knowing and loving co-emerge.

Phenomenal description: What does ‘cosmic joy’ feel like?

Spinoza’s description of beatitude is grounded in affective language even though his method is rational. Phenomenally, readers often report something like:

- A widening of attention: the sense of individual boundaries softens while distinctiveness remains clear.

- A calmened urgency: anxieties tied to imagined contingencies diminish; one feels steadier.

- A luminous clarity: thoughts feel less clouded by fragmentation; causes and relations appear meaningful.

- Joy that is not fleeting: rather than spike-like pleasure, there is a steady, reflective delight—an appreciation of necessary order and beauty.

Different from theistic mystical union, Spinoza’s peace is impersonal and explanatory: you don’t lose individuality into a personified God; you see your activity as an instance of a universal order and respond with rational love—hence ‘intellectual love.’

Rational-mystical bridge: How can a naturalistic rationalism feel mystical?

The paradox dissolves when we separate ‘mystical’ as purely supernatural from ‘mystical’ as an intense, non-ordinary quality of knowing. Spinoza’s system produces experiences labeled mystical because they intensify affect while preserving cognitive clarity. The ‘mystery’ arises from the mind’s direct, immediate sense that disparate things belong together—an aesthetic-cognitive gestalt. So the bridge is: rigorous knowledge (third kind) → immediate perception of unity → affective response (joy) that we can call ‘mystical’ without invoking supernatural claims.

Comparative notes: Where Spinoza sits among mystics

- Plotinus (Neoplatonism): Plotinus’s mystical ascent dissolves individuality into the One. Spinoza’s unity is immanent; the mind does not annihilate itself but understands its place.

- Meister Eckhart: Both emphasize union with God, but Eckhart retains a personal, theistic tone; Spinoza reframes union as comprehension of nature’s necessity.

- Buddhism (certain readings): Shared themes—less clinging, clearer perception, insight into dependent origination—yet Spinoza remains metaphysically committed to a single substance, not no-self doctrines.

- Modern spiritual-but-not-religious approaches: Spinoza provides a rigorous intellectual backbone to experiences often described in contemporary spirituality—wonder, awe, interconnectedness—without leaving naturalism.

Modern resonance: psychology, neuroscience, and practice

Empirical parallels: contemporary research on contemplative practices shows correlations between insight-oriented practices and improved well-being. Meta-analyses of mindfulness-based interventions report moderate effect sizes for reduced anxiety and depression and improved emotional regulation (pooled effect sizes typically in the small-to-medium range). Social neuroscience on awe and connectedness shows shifts in self-referential processing and prosocial motivation.

But: Spinoza’s path is distinct. It centers on cultivating adequate ideas—not only calming attention but transforming cognition. Practices inspired by Spinoza might therefore combine reflection, conceptual clarification, and contemplative attention.

Creative-practice takeaways for thenoetik readers

- Treat philosophical study as a contemplative discipline: slow reading, journaling, and analogy-making are practices that cultivate adequate ideas.

- Use aesthetic experiences (art, nature) as triggers for seeing relations—then analyze them conceptually to convert felt insights into sustainable understandings.

- Pair inquiry with embodied regulation: breath, posture, or brief attentional exercises help stabilize the mind so that insight can land.

Critiques and limits: Honest Caveats

- Determinism and agency: Spinoza’s determinism troubles some readers. If all is necessary, can we meaningfully speak of responsibility or ethical change? Spinoza answers by redefining freedom as acting from adequate ideas, but objections remain.

- Reductionism vs. richness of affect: Critics say Spinoza explains away religious feelings as cognitive states. Spinoza would reply that explaining affect does not diminish its value; it transforms it into enduring beatitude.

- Philosophy alone may not suffice: Intellectual insight can shift experience, but for many people, embodied and social practices mediate lasting change. Expect philosophy to be a catalyzing—not always a single—path.

Practical section: Exercises & Prompts

- Three-minute ‘Relation Scan’: Sit with a simple object (leaf, mug). Note its properties. Ask: how does this object depend on environment, materials, history? Write two causal relations. Aim to move from ‘it’s beautiful’ to ‘its beauty arises from X, Y, Z.’ (Cultivates adequate ideas.)

- Stoic/Spinozan Reframe: When anxious, identify the imagined future causing the affect. Trace one causal belief behind it and rewrite that belief as a neutral explanation of necessity. Notice whether intensity drops.

- Awe-to-Insight practice (10 minutes): In nature or before art, let attention widen. After 5 min of open attention, spend 5 min writing down structural relations you perceive. Convert one felt insight into a concise explanatory claim.

- Journaling prompt (thenoetik-style): ‘Where did I feel small and where did I feel connected today? Can I describe a causal connection that links them?’

- Weekly Reading Ritual: Read one short proposition from Ethics (e.g., Part II or V) slowly. Paraphrase it in your own words and list one way it could change a decision this week.

Further reading and primary-text citations (short annotated list)

- Spinoza, Ethics (Ethica): read Part II (on the nature of the mind), Part III (on the emotions/affects), and Part V (on the power of the intellect and beatitude). Key passages: Ethics, Part II (on knowledge), Part III (on affects), Part V (on amor intellectualis Dei and beatitudo). These sections map the pathway described above.

- Jonathan Bennett, A Study of Spinoza’s Ethics — accessible guide to arguments and structure.

- Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy — contemporary philosophical treatment emphasizing immanence and joy.

- Lisa Shapiro, ‘Spinoza and the Stoics’ — helpful for comparative and ethical context.

- Neuroscience meta-analyses on mindfulness and well-being (see e.g., Khoury et al., 2015 for overview) — for empirical context linking contemplative practice to affective change.

Primary-text quotations (short):

- ‘Deus sive Natura’ (Spinoza, Ethics and other works) — Spinoza’s formula for divine immanence.

- ‘amor intellectualis Dei’ (Ethics, Part V and related passages) — Spinoza’s name for the intellectual love that forms beatitude.

- Paraphrase anchor: Spinoza insists that understanding the order of things increases love and blessedness (Ethics, Part V, see propositions on intellectual love).

Note: for academic citation, consult a reliable edition of the Ethics (e.g., Edwin Curley translation) and locate the passages in Parts II–V.