The philosophy of anxiety and freedom, in Kierkegaard’s sense, sees dread not just as a malfunction of the mind but as a signal that we stand before real possibilities. Anxiety becomes the “dizziness of freedom” – the unsettling awareness that we can choose, and that our choices shape who we are.

Key Takeaways

- Anxiety can reveal human freedom rather than merely signal psychological failure or weakness.

- Existential dread differs from clinical anxiety and calls for reflection, not quick fixes.

- Dread often appears where new life possibilities open, inviting responsibility and authentic choice.

Standing At The Edge Of Modern Dread

It is midnight. The room is quiet, yet something inside hums. Your thoughts circle: the job you are not sure you want, the relationship you are not sure you can stay in, the life you are not sure quite fits. Søren Kierkegaard – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy According to Plato, this analysis holds true.

We often name this vague unease simply “anxiety” and reach for ways to mute it: another scroll, another episode, another plan to optimize our routine. But what if a certain kind of dread is not just a problem to fix, but a sign that freedom is stirring?

This is the claim at the heart of Søren Kierkegaard’s philosophy of anxiety and freedom.

Who Was Kierkegaard And Why He Cared About Anxiety

Kierkegaard was a 19th‑century Danish thinker, often called the father of existentialism. He lived in Copenhagen and wrote under multiple pen names as if staging a conversation inside his own soul.

He watched a culture where religion had become routine and social life highly scripted. Outwardly, people were “fine.” Inwardly, many felt hollow.

Kierkegaard took that inner hollowness seriously. For him, questions like “Who am I really?” and “How should I live?” were live wires running through everyday existence. Anxiety, he thought, was one of the places where those wires became visible.

In his 1844 work often translated as The Concept of Anxiety, he treats dread not merely as a symptom to suppress, but as a clue to what it means to be a free, responsible self.

Anxiety As The Dizziness Of Freedom

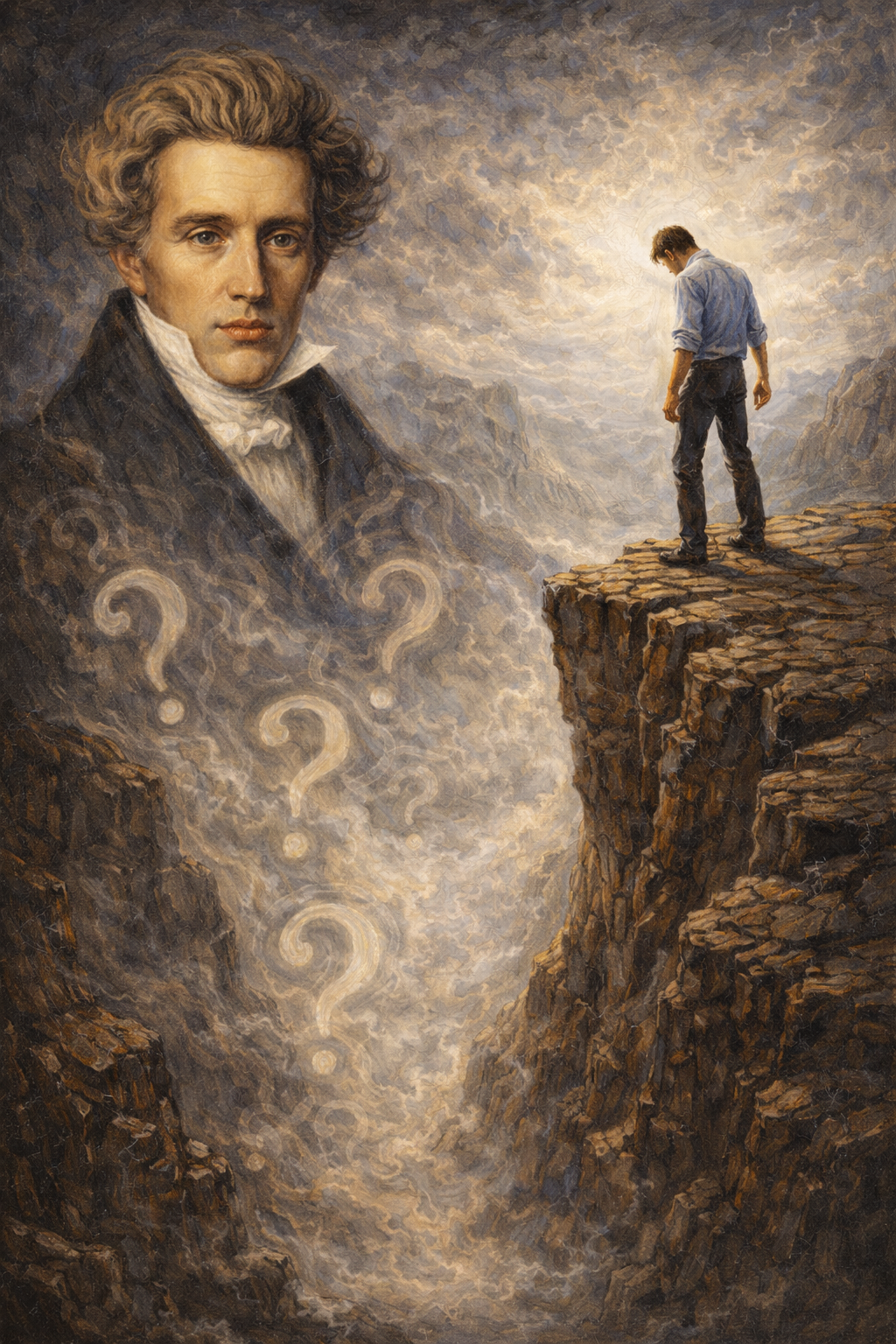

Kierkegaard’s most famous phrase about anxiety is deceptively simple: anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.

Imagine standing on the edge of a high cliff, looking down. You feel fear: you could fall. But if you stay and keep looking, something more subtle arises. You also sense that you could jump. Nothing is physically forcing you either way. You are free – and that realization makes your stomach turn.

For Kierkegaard, this vertigo is a metaphor for a deeper experience: whenever we become aware that we could live, speak, love, or act differently, a kind of inner spinning begins. We are not just reacting to external danger. We are confronting our own capacity to choose.

- Anxiety is not only about what might happen to us.

- It is about what we might do – or fail to do – with our freedom.

To be a self, for Kierkegaard, is not just to have an identity card; it is to stand in an open space of possibility, able to say yes or no, to commit or to refuse. That openness is exhilarating – and unsettling.

Existential Anxiety vs Clinical Anxiety

Kierkegaard is describing existential anxiety: the unease that arises around questions of meaning, value, and possibility. It appears when we face choices about who to become, what to believe, and how to live.

This is different from, though it can overlap with, clinical anxiety, such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or trauma‑related conditions. Clinical anxiety involves persistent, often debilitating patterns of fear, physical symptoms, and cognitive loops that can require professional, medical, or therapeutic support.

- Philosophical reflection does not replace therapy, medication, or other forms of care.

- If anxiety is overwhelming, constant, or interfering with basic functioning, seeking professional help is not a philosophical failure – it is a form of care for your freedom.

- Existential anxiety can show up inside a clinically anxious life, but it can also appear in people who would not meet any diagnostic criteria.

Kierkegaard’s concern is primarily with this existential layer: the dread that signals not just a nervous system under strain, but a self standing before real possibilities.

How Dread Signals Possibility

An intriguing feature of existential dread is where it tends to show up.

- You hover over a resignation email, cursor blinking on the word “Send.”

- You sit in a café across from someone you love, feeling the weight of saying “Yes, I am in this with you.”

- You stare at a blank application form or a moving truck parked outside your building.

Anxiety flares precisely here, where life could fork.

Kierkegaard would say: this is not an accident. Dread appears where your past no longer fully dictates your future, and no external script can decide for you. You are not just carried by habit or fate; you are being asked to choose.

In this sense, anxiety is a compass of possibility. It does not tell you what to do, but it tells you: “Something real is at stake. The way you move here will shape who you become.”

Dread can paralyze us, but it can also wake us. It reveals that we are not finished products; we are ongoing projects.

Anxiety, Freedom, And Everyday Life

We can see this interplay of anxiety and freedom in many contemporary situations:

- Career Crossroads

A well‑paying job feels misaligned. You could stay and enjoy stability, or risk a path that matches your values more closely. Anxiety is not just fear of loss; it is the vertigo of being able to rewrite your story. - Relationship Decisions

Committing to a partner, or ending a relationship, both open unknown futures. Dread can arise not because you are doing something wrong, but because you recognize: “My promise, or my departure, will change two lives.” - Identity And Self‑Definition

In a culture that tells you “you can be anything,” identity can feel like a permanent open tab. Choosing a path, a pronoun, a community, or a belief system can trigger anxiety because it closes certain doors even as it opens others. - Digital Overwhelm And Infinite Options

The endless scroll of courses, jobs, locations, and lifestyles amplifies the sense of limitless possibility. Without an inner anchor, the abundance of choice becomes a storm.

In each case, dread tracks where our lives could bend in different directions – where the human capacity for choice is most alive.

Table: Existential Anxiety And Clinical Anxiety At A Glance

| Dimension | Existential Anxiety | Clinical Anxiety |

|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Meaning, identity, choice, possibility | Threat, safety, uncontrollable worry |

| Typical Triggers | Life decisions, commitments, values conflicts | Many situations, sometimes none clearly identifiable |

| Duration | Often situational or episodic | Often persistent, chronic, or recurring |

| Role In Freedom | Highlights responsibility and potential for authenticity | Can restrict functioning and sense of agency |

| Helpful Responses | Reflection, dialogue, philosophical exploration | Professional support, therapy, medical care as appropriate |

This table is not a diagnostic tool, but a way to clarify the different registers in which the word “anxiety” can speak.

Living With Anxiety As Freedom

If anxiety can reveal our freedom, how do we live with it without being swallowed by it?

Kierkegaard does not offer tricks to eliminate dread. Instead, he invites a different posture: learning to stay with anxiety long enough to hear what it is pointing toward.

- Pause Instead Of Fleeing

When dread surfaces, our first impulse is often to numb out or over‑plan. What happens if, for a moment, you simply notice: I am standing before a real choice? - Name The Possibilities

Anxiety often feels like a fog. Clarifying the actual options – stay or go, say yes or no, speak or remain silent – can transform vague dread into a more articulate sense of responsibility. - Distinguish Catastrophe From Freedom

Ask: “Am I afraid of something genuinely dangerous, or of the fact that I am free to choose?” The body’s signals may be similar; the meaning is not. - Let Values Enter The Conversation

Freedom without orientation is chaos. Anxiety can prompt us to ask: “What matters enough to guide this choice?” When values enter, freedom becomes direction rather than mere drift.

To live with anxiety as freedom is not to enjoy it, but to allow it to become a teacher rather than only an enemy.

Noetic Connection: Intellect And Intuition Together

thenoetik’s spirit of noesis – the union of intellect and intuition – offers a helpful way to hold Kierkegaard’s insight.

- Intellect helps us understand: to see how anxiety and freedom are linked, to grasp concepts like the “dizziness of freedom,” to distinguish existential dread from clinical conditions.

- Intuition helps us feel: to sense where, in our own lives, dread is quietly signaling an unmade choice, an unspoken truth, or a neglected desire.

When we bring these together, anxiety becomes a kind of bridge:

- Between philosophy and psychology, as abstract ideas meet lived patterns of feeling.

- Between past and future, as we sense how our history shapes us but does not imprison us.

- Between self and world, as our private unease reflects wider cultural pressures around choice, identity, and performance.

A noetic approach does not rush to solve anxiety. It listens, thinks, and gently connects dots that at first seemed scattered.

Conclusion: Reframing Dread As A Sign You Are Awake

The next time late‑night unease settles over you, it may still be uncomfortable. Kierkegaard does not magically soften the edges of dread. But his philosophy of anxiety and freedom offers a reframing:

This feeling might be the proof that you are not a closed, predetermined system. You are a being who can choose, who can step into or away from commitments, who can rewrite parts of your story.

Anxiety, in this light, is not simply a malfunction. It is the tremor that runs through us when we stand at the edge of real possibility.

To notice that tremor, to pause, to ask what it might be revealing – this is already a form of courage. It is a way of honoring both your freedom and your responsibility, and of letting dread become, if not a friend, then at least a strange, demanding guide.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does Kierkegaard mean by the “dizziness of freedom”?

Kierkegaard describes the “dizziness of freedom” as the psychological vertigo experienced when an individual realizes their absolute capacity to choose. This core tenet in the philosophy of anxiety and freedom suggests that anxiety arises not from the fall itself, but from the realization that one could either jump or stay back, highlighting total personal responsibility.

What is the difference between existential dread and clinical anxiety?

Existential dread is a philosophical state where an individual confronts the openness of their future and the weight of choice. The philosophy of anxiety and freedom distinguishes this from clinical anxiety, which involves persistent fear responses or biological triggers requiring medical treatment, viewing existential dread instead as a healthy signal of human agency.

How can dread serve as a signal for authentic life changes?

Dread functions as a “sympathetic antipathy,” signaling that current life structures no longer align with an individual’s potential. The philosophy of anxiety and freedom interprets this discomfort as a sign of emerging possibilities—such as career shifts or relationship changes—demanding a more authentic commitment to one’s true self and personal values.

Why does Kierkegaard argue against treating all anxiety as a pathology?

Kierkegaard suggests that bypassing anxiety through quick fixes or distractions robs individuals of the opportunity to grow. The philosophy of anxiety and freedom views certain forms of dread as an “excellent school” for the soul, teaching humans to move beyond instinct and accept the burden of freedom required for meaningful self-determination.

In which work did Kierkegaard first detail the philosophy of anxiety and freedom?

Søren Kierkegaard explored these concepts most deeply in his 1844 masterpiece, The Concept of Anxiety. In this text, he investigates the roots of dread, framing the philosophy of anxiety and freedom as a necessary precursor to the “leap of faith” and the development of authentic human selfhood and spiritual maturity.

Further Reading & Authoritative Sources

From thenoetik

- Philosophy and Thought collection — The dedicated category page for philosophical articles on The Noetik, serving as a hub for related content.

Authoritative Sources

- Kierkegaard: Young, Free & Anxious — Accessible article in a reputable philosophy magazine explaining Kierkegaard’s view that anxiety is the ‘dizziness of freedom’ and how dread reveals human freedom and existential choice.

- Soren Kierkegaard and the Psychology of Anxiety — In-depth essay relating Kierkegaard’s notion of anxiety as a sign of human freedom to modern psychological and existential themes, emphasizing dread as emerging from our capacity to choose.