How Klimt Used Gold Leaf: Ritual, Technique & Meaning

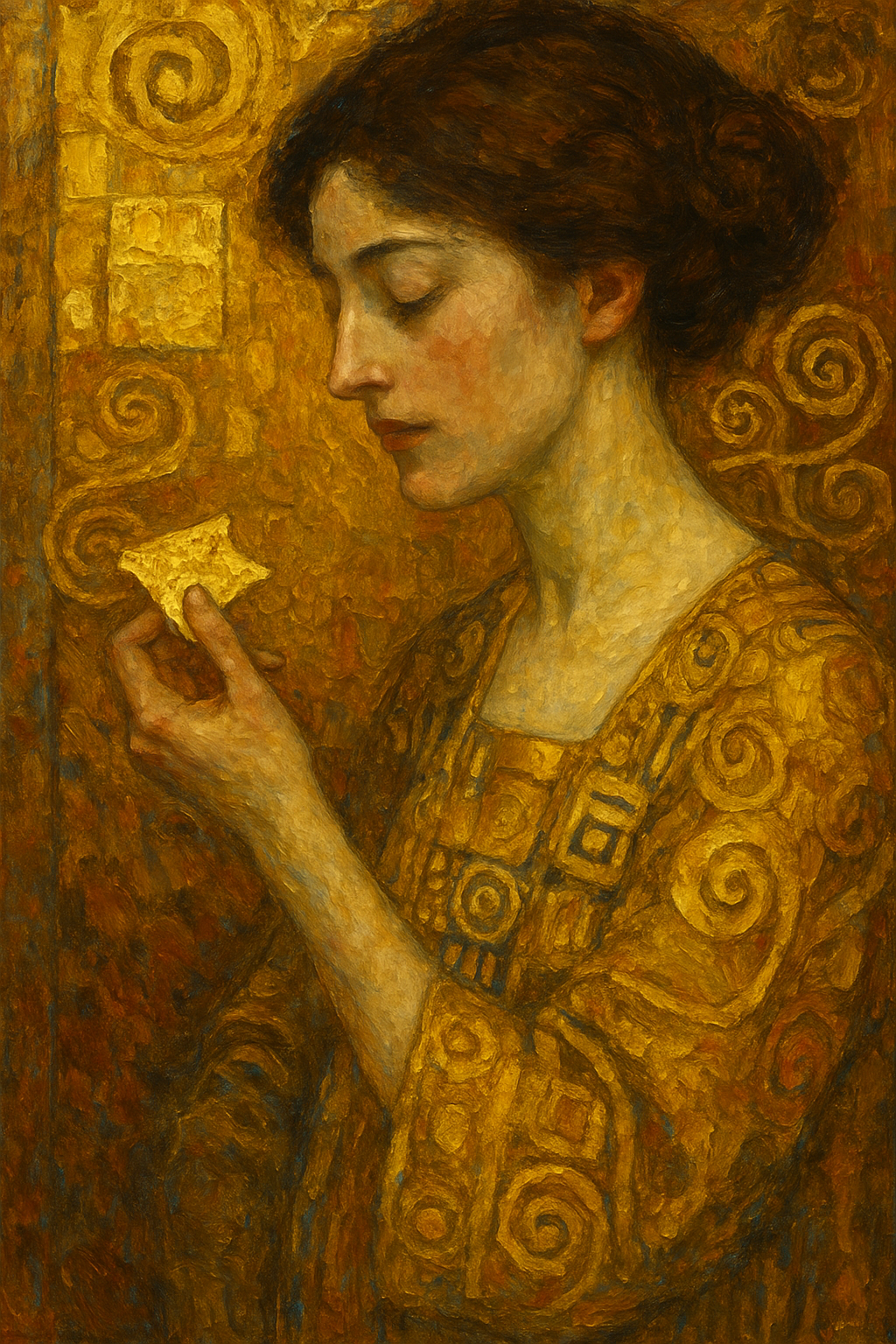

Imagine Gustav Klimt at a low table, a sheet of gold leaf trembling in the studio light, and a fine brush laying mordant with near‑ceremonial care. In asking how Klimt used gold leaf, we discover a practice that was technical, performative, and philosophical — a ritualized method that fused craft with modern psychology.

Key takeaways:

* Technique was ritual: Klimt combined water‑mordant and oil gilding, burnishing, and mixed media to make gold integral to composition.

* History was his muse: Byzantine mosaics, medieval illumination, and Japonisme converged in his Golden Phase of Klimt.

* Gold is symbolic: Klimt used gold to signal the sacred, the erotic, and the idea of immortality.

* Gold changes perception: reflective surfaces slow viewing and fuse intellect with intuition (noesis).

> Klimt’s gold is not ornament alone; it is a luminous grammar that reorients what we think and what we feel.

How Klimt Used Gold Leaf: Ritual & the Golden Phase

Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) led the Vienna Secession and, during his Golden Phase, made gold leaf a central language of painting. Fin‑de‑siècle Vienna — psychoanalysis, modern music, and aesthetic renewal — shaped his need for a visual device that could suspend figures in a timeless, sacred field. Thus, gold became less a surface and more a ritual of seeing.

That ritual quality extended beyond technique to presentation. Klimt often staged his gilded pictures so that moving about a room changed the way the gold read: at certain angles details would flash or recede. This performative relationship between viewer and picture was intentional — an empirical element of his pictorial grammar. Conservators and curators have repeatedly observed that Klimt planned these viewing dynamics from preparatory drawings through to varnish and framing decisions, making how Klimt used gold leaf as much about choreography as it was about adhesion.

How Klimt Used Gold Leaf: Techniques and Materials

So, precisely how Klimt used gold leaf: his approach married traditional gilding with painterly invention. Conservators at museums such as the Belvedere and the Leopold Museum confirm layered practices that were planned from early design stages.

* Grounds and supports: canvases or panels prepared with gesso or glue‑size to accept mordant.

* Mordant and oil gilding: Klimt used both water‑based mordant (for burnished, mirror finishes) and oil‑based methods (when painting over leaf was needed).

* Mixed‑media and tesserae: glass, mother‑of‑pearl, and metal powders were often embedded to mimic mosaic effects.

* Burnishing vs. matte: polished gold reflects like a mirror; matte leaf or painted-over gold softens the shine — Klimt used contrasts to direct the eye.

Technical imaging (X‑radiography, infrared reflectography) shows gilding plans integrated into underdrawing, confirming these gilding choices were conceptual rather than decorative afterthoughts.

A short case example: microscopic cross‑sections from Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I show a multi‑layer build up — ground, mordant, several leaves, and protective coatings — that together produce the jewel‑like depth that defines many of Klimt’s major works. Such stratigraphy demonstrates how he exploited modern materials (pigment varnishes, synthetic adhesives that started appearing in the late 19th century) alongside time‑honored gilding recipes.

Historical Influences: Byzantium, Japonisme, and Illumination

Klimt’s gilding draws on a lineage of visual practice:

* Byzantine mosaics: the shimmering gold ground removes temporal depth and creates a sacred plane.

* Medieval illuminated manuscripts: burnished folios made text sacred; Klimt made picture planes similarly consecrated.

* Japonisme: Japanese screens flattened space and emphasized pattern; Klimt absorbed this surface logic into his compositions.

These influences were synthesized, not copied, resulting in a modern idiom where ornament and figure cohere. Comparative analysis highlights that while Byzantine mosaics create space by removing pictorial depth, Klimt reverses that logic: gold becomes the space in which psychological depth unfolds. In this sense, how Klimt used gold leaf is both homage and radical reinvention.

The Rich Symbolism in Klimt’s Art: Sacred, Erotic, Immortal

Why Klimt used gold reaches beyond materials. In his hands gold became polyvalent:

* Sacred/hieratic: a gold ground consecrates portrait and allegory, lifting subjects into mythic time.

* Eroticism and veil: ornament both reveals and screens flesh, turning eroticism into a ritualized aesthetic.

* Immortality and alchemy: gold resists corrosion; it gestures toward transfiguration and permanence.

Together, these readings show how Gustav Klimt gold leaf paintings ask the viewer to read surface as idea. In practice, the reflective quality of gold modifies color relationships: skin tones read warmer against gold, and color saturation appears heightened. This chromatic alchemy is central to understanding why and how Klimt used gold leaf as a visual and symbolic engine.

Masterpieces: Close Readings (Gustav Klimt gold leaf in practice)

The Kiss (1907–08) — The Kiss as Ritual

A couple wrapped in patterned golden robes floats against a field of gold. Ornament collapses background and garment into a single luminous matrix. The gilding turns intimacy into a sacrament, an emblem of Klimt’s Golden Phase.

Beyond its symbolic reading, The Kiss is instructive technically: Klimt varied the texture of leaf application to separate figure and pattern, using burnished sections to catch highlights and powdered metal or painted glazes to mute others. The result is an image that reads differently at arm’s length and up close.

Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I (1907) — Gold and Iconicity

Called the Woman in Gold, Adele’s painted face and hands emerge from an intricate gold ground. Here, Klimt borrows Byzantine concepts to elevate portraiture into near‑iconic status — an explicit use of gold to transfigure the subject.

This painting also serves as a case study in conservation and cultural history: after restitution, careful examination and restoration were performed to respect Klimt’s original choices of alloy and technique, underscoring how legal and ethical histories intersect with material care.

Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1901) — Gold, Violence, and Desire

Gold intensifies the work’s paradox: sanctified violence and erotic triumph. The shimmering field makes the biblical narrative feel mythic and psychological.

Beethoven Frieze (1901) — Public Gilding and Mosaic Logic

A large allegorical frieze uses gold, silver, and glass tesserae; gilding functions architecturally, organizing procession and turning wall into luminous scripture.

The frieze shows how Klimt applied gilding at scale — with mosaic references and material diversity — to create immersive, site‑specific experiences.

How Klimt Used Gold Leaf: Conservation Science and Findings

Modern conservation confirms mixed methods:

* Layer structure: cross‑section microscopy documents adhesive grounds, leaf, and varnish layers; both mordant and oil gilding are present across works.

* Underdrawing and planning: imaging shows gilded areas integrated early in composition.

* Aging: gold is chemically stable, but adhesives, alloys, and included materials may change — conservation must respect Klimt’s intended contrasts.

These technical results reinforce interpretive claims that gilding was conceptually central.

Conservators now face complex questions: when a gilded surface has darkened due to aged varnish or degraded binding media, should treatment seek to restore the original sparkle or to preserve the object’s historical patina? Museum practice increasingly favors minimal intervention that clarifies without falsifying Klimt’s layered intentions. As one conservation scientist has noted in technical literature, Klimt’s use of different gilding systems within a single work requires a tailored approach to consolidation and cleaning.

Cultural Legacy: Klimt-Inspired Gold Leaf Home Decor and Market Effects

Klimt’s gilded imagery now informs fashion, design, and interiors. Searches for Klimt prints and Klimt The Kiss gold leaf reproductions show persistent commercial interest. At the same time, museums developed specialized conservation protocols for mixed‑media gilded paintings — a technical legacy as well as an aesthetic one.

Practical applications have followed: designers use gilded motifs in textiles and wallpaper; jewelers and ceramicists reference Klimt’s palettes and patterning; digital artists echo the effect through metallic shaders and post‑processing filters. Even augmented reality (AR) installations have adapted Klimt’s visual language, simulating moving light across a gilded plane — a contemporary echo of Klimt’s original concern with how light animates ornament.

Practical Guide: How to Try Klimt‑Style Gilding (Step‑by‑Step)

If you want to experiment safely with a Klimt‑inspired gilded effect, try this simplified studio exercise. Note: this is for creative exploration, not conservation‑grade painting.

Materials:

* Prepared panel or heavy canvas

* Acrylic gesso or rabbit‑skin glue (for traditional grounds)

* Gold size (water or oil‑based) and imitation composition leaf or real leaf (composition leaf is cheaper and easier for beginners)

* Soft brushes, burnisher (agatis or bone), cotton gloves

* Protective mask and ventilated workspace

Steps:

1. Prepare the ground: apply two to three thin coats of gesso and sand for smoothness. Klimt used very smooth supports to take leaf cleanly.

2. Transfer your design with light underdrawing; plan gilded areas carefully.

3. Apply size: for a burnished finish use water‑based or glue size; for overpainting use oil size. Follow manufacturer drying times — tack must develop but not fully dry.

4. Lay leaf: using a soft brush or gilder’s tip, lay pieces gently and press to adhere. Overlap seams and lay grain with attention to pattern direction.

5. Burnish selectively: once the size is ready, burnish areas you want reflective. Leave some passages matte for contrast.

6. Add paint and pattern: use thin glazes or metallic paints to integrate gold into imagery. Klimt often painted on top of gold, so layering is key.

7. Seal lightly if desired with a conservation‑grade varnish; consult material safety data sheets for compatibility.

Safety tip: avoid breathing fine metal powders and work in a ventilated space. Wear gloves to minimize oils from skin transferring to leaf.

Comparative Analysis: Klimt vs. Contemporaries and Earlier Traditions

Klimt’s gilding stands apart from the heavy, iconographic use of gold in medieval art because of its modern psychological aims. Compared with contemporaries like Egon Schiele, who pursued raw line and expression, Klimt returned to ornament and material luxury to tackle similar themes — desire, mortality, and identity — but through surface rather than gesture. In Europe’s larger decorative arts movement (Art Nouveau), Klimt’s gold is both an aesthetic kin and a radical personalization: ornament becomes an existential stage rather than mere embellishment.

Future Trends & Predictions

Looking forward, Klimt’s gilding will likely continue to inspire interdisciplinary projects:

* Digital art and AR/VR will simulate gilded surfaces more convincingly, enabling dynamic lighting that recalls Klimt’s viewing choreography.

* Conservation science will apply non‑invasive imaging and materials analysis to map gilding recipes at micron scales, informing both scholarship and practice.

* Designers will rework Klimt’s motifs into sustainable materials (bio‑metallic foils, recycled composites), balancing visual opulence and environmental concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why did Klimt use gold leaf so often?

Klimt used gold leaf to create a luminous field that consecrated portraiture and allegory. Gold signaled permanence, ritual, eroticism, and the alchemical idea of transfiguration; conservation reports show he integrated gilding into composition early on.

What techniques did Klimt use for gilding?

He used both water‑based mordant (for burnished shine) and oil gilding (for painting over leaf), mixed media (glass, metal powders), and contrasted burnished and matte surfaces to control light and focus.

Are Klimt’s gilded paintings fragile?

Gold itself resists corrosion, but adhesives, metal powders, and integrated materials can deteriorate. Museums use reversible, minimal interventions and climate control to preserve these works; consult Belvedere and Neue Galerie technical notes for details.

Which works best display Klimt’s gilding practice?

Key examples: The Kiss; Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I; Judith; Beethoven Frieze — each demonstrates different technical and symbolic uses of gold.

How can I learn Klimt gold leaf techniques at home?

Basic gilding involves a prepared ground, adhesive size, and careful laying of leaf. For Klimt‑style effects, study mixed‑media approaches and work with imitation composition leaf and appropriate sizes; beginner tutorials and gilding supplies for Klimt‑style art are widely available.

How do museums decide whether to clean or conserve gilded areas?

Conservators weigh the artist’s intent, material stability, and historical patina. They prioritize non‑invasive analysis (imaging and microsampling) and prefer treatments that are reversible and well‑documented.

Can I buy real Klimt gold leaf reproductions?

Authentic Klimt originals are in museums and private collections; reproductions vary widely in quality. Look for high‑quality giclée prints with applied metallic leaf or certified limited editions from reputable publishers if you want a faithful decorative reproduction.

Conclusion: An Invitation to See Differently

Klimt’s use of gold leaf was a ritualized practice — a method of seeing that fused intellect and intuition. By studying how Klimt used gold leaf, we learn how a material can reorient perception and make an image think back at us. We leave you with a micro‑practice: hold a small metal object, notice how light shapes it, and consider how brightness guides meaning. How does that change what you see?