AI models hallucinate because they are built to generate the most plausible next words, not to check what is true. Trained on vast text and rewarded for fluency and helpfulness, they sometimes invent details with great confidence. These fabrications are structural side effects, not a simple fixable bug.

- Hallucinations arise from how language models generate likely text, not from glitches.

- Models lack built-in truth-checking; they optimize for coherence and confidence instead.

- Working wisely with AI means pairing its patterns with our judgment and verification.

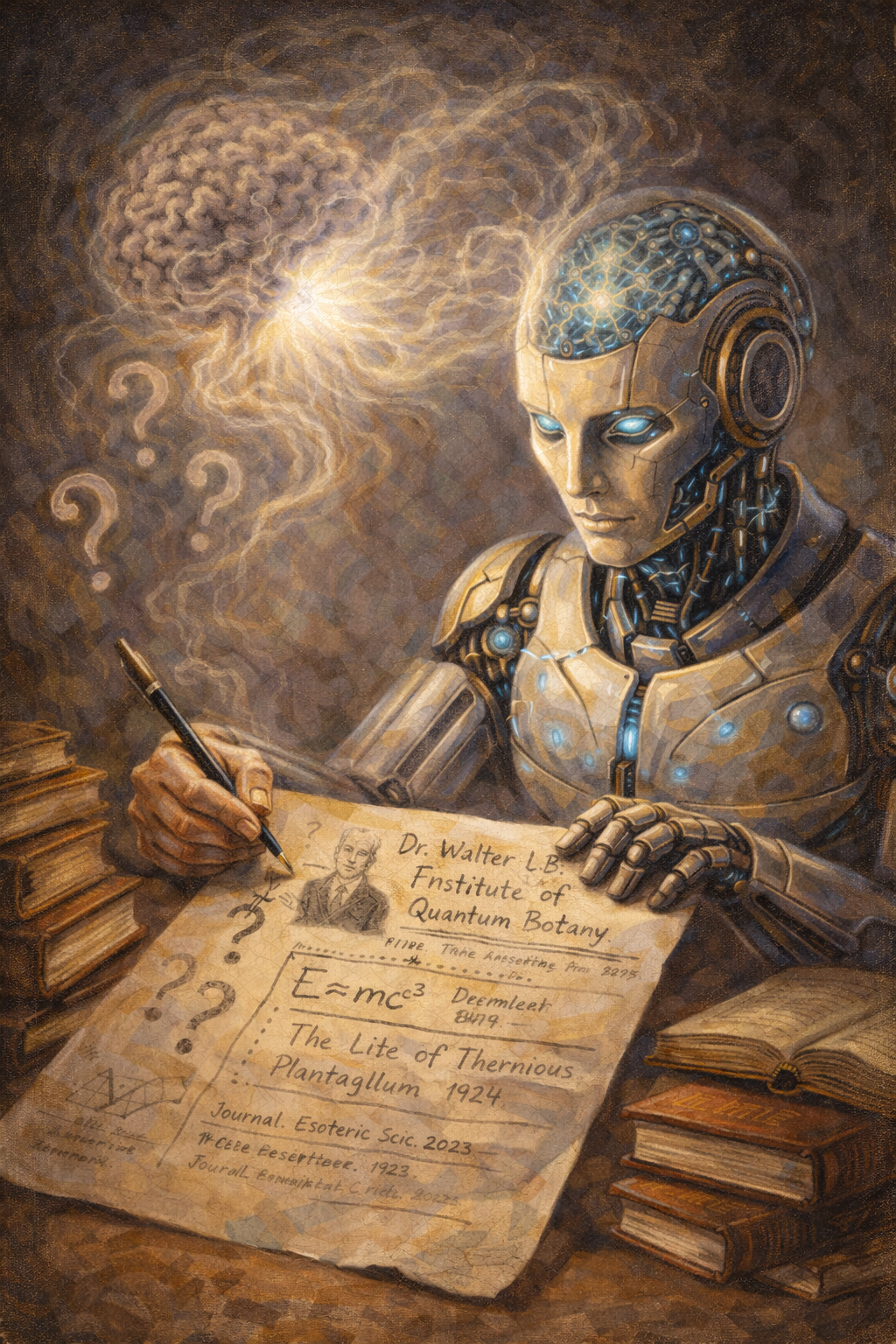

Rethinking Hallucinations As A Window Into AI

When we ask why do AI models hallucinate, we often imagine a fixable defect—like a bad line of code waiting for a patch. But hallucinations are more like fingerprints: marks left by how these systems are fundamentally built to work.

Instead of treating them as accidents, we can read hallucinations as clues. They show us what large language models actually do: they do not “know” the world; they model patterns in language about the world. That difference is everything.

What Are AI Hallucinations, Really?

In everyday use, an AI hallucination is a fluent, specific answer that sounds right but is not grounded in reality.

- You ask for a scientific paper; it gives you a perfectly formatted citation—journal, year, volume—that simply does not exist.

- You request a summary of a book; the book is real, but key scenes the model describes never appear in it.

- You query a niche concept; the model confidently invents a technical term and backstory to fill the gap.

These are not just small mistakes, like a typo in a date. They are fabricated structures: names, quotations, or events composed out of patterns in the training data, then presented as fact.

We can distinguish them from other errors:

- Outdated information: The model reports last year’s CEO or policy because its training data stops at a certain point. That answer was once true.

- Simple miscalculation: It slips on arithmetic. That is a narrow, mechanical error.

- Hallucination: It invents something that was never true at any time, but that fits the style and structure of things that are.

To understand why that happens, we have to look at how these models actually work.

How Large Language Models Work In Essence

At their core, large language models are next-word predictors. Given some text, they estimate which word (or piece of a word) is most likely to come next, based on what they have seen across enormous training corpora.

Roughly, training looks like this:

- Collect vast amounts of text: books, articles, websites, code, dialogue.

- Hide some words and ask the model to guess them.

- Adjust the model’s internal parameters to make its guesses more accurate over millions or billions of examples.

Over time, it becomes extremely good at modeling patterns: how concepts tend to connect, how arguments are structured, which phrases follow which questions.

Notice what is missing: there is no direct line to the world itself. The model does not see experiments, objects, or events—only texts humans have written about them. It is learning the shape of language, not the nature of reality.

So when you type a question, the model does not consult a mental map of facts. Instead, it performs a sophisticated form of autocomplete: producing the sequence of words that, in its statistical experience, best fits your prompt and the style you seem to want. This makes it incredibly versatile—and inherently fragile when facts matter.

Why Hallucinations Are Structural, Not Accidental

Once we see the model as a pattern machine optimizing for plausible text, hallucinations stop being surprising. They become almost inevitable.

Several structural forces push in that direction:

Always Say Something

Language models are trained to always produce an answer. Silence is not rewarded. When the model is unsure—because the question is obscure, ambiguous, or outside its training—it still has the same job: continue the text. The result: instead of “I do not know,” you often get the most plausible guess assembled from similar patterns it has seen.

Fluency Is Rewarded, Not Truth

During training and later fine-tuning, models are reinforced for being helpful, polite, and coherent. Human evaluators often prefer:

- Confident, detailed answers over hesitant ones

- Complete stories over fragmentary replies

This nudges the model toward confident completion, even when its internal signal about likelihood is weak. The system is not optimizing for “Is this true?” but for “Does this look like the kind of answer people like?”

Gaps And Overgeneralization

No dataset covers all of reality. There will be missing people, places, studies, and niche facts.

When confronted with a gap, the model often generalizes from nearby patterns:

- If many researchers in a field have similar-sounding names and affiliations, it might hallucinate a new one that fits the pattern.

- If many books in a genre share structures, it might invent chapters and characters that feel right but never existed.

No Built-In Reality Check

Crucially, there is no internal module in the core model that checks its outputs against a database, the web, or the physical world. Unless explicitly connected to external tools, the model’s only reality is its training text and the statistics it learned.

So when we ask why do AI models hallucinate, the sober answer is: because nothing in their native architecture forces them not to. Truth is, at best, an emergent side effect of good pattern modeling, not the primary target.

Human Mind Analogies And Where They Break

The word “hallucination” tempts us to anthropomorphize: is the AI dreaming, fantasizing, lying? Here the comparison with human minds is helpful—but only if we handle it carefully.

Shared Patterns: Confabulation And Narrative

Humans also confabulate. We misremember details, fill gaps in memories with plausible stories, or confidently recall events that never happened. Our brains are narrative machines, stitching fragments into coherent wholes.

In that sense, AI hallucinations mirror us:

- Both are pattern-based completions of incomplete information.

- Both favor coherent stories over true but messy uncertainty.

We might even see models as externalized fragments of our own cognitive habits—trained on our texts, echoing our strengths and distortions.

Fundamental Differences: No Experience, No Intention

But the analogy has strict limits:

- A human hallucination involves subjective experience—perceiving something that is not there. Models have no inner theater; they manipulate symbols.

- Humans can intend to deceive or to seek truth. Models have neither intention nor belief. They do not know they are wrong.

So while the term “hallucination” is poetic, a more precise picture is statistical fabrication. Still, the comparison to human error is philosophically fruitful: it asks us what we really mean by “knowing” in both minds and machines.

Not A Bug But A Design Constraint

Can we just turn hallucinations off? Not without changing what the model is.

If you ask a system whose essence is “continue the text in a plausible way” to suddenly refuse to guess, you are pulling against its core design. You can dampen, redirect, or constrain, but not erase the tendency entirely.

Today, several mitigation strategies are layered around models:

- Retrieval-augmented generation: The model first fetches documents from curated sources, then generates answers based on those. This anchors responses in external evidence.

- Tool use: For math, dates, or current events, the model can call calculators, search engines, or databases instead of guessing.

- Guardrails and policies: Systems are tuned to say “I do not know” more often, avoid speculative claims, or flag uncertain outputs.

These approaches reduce hallucinations, especially in well-covered domains. But they have limits:

- Retrieval only helps if relevant, accurate documents exist and are found.

- Tools must be correctly chosen and integrated.

- Guardrails are trade-offs: the more cautious the model, the less creative and free-flowing it may feel.

So hallucination is better understood as a design constraint. We can build architectures and workflows that lean against it, but we cannot entirely remove it while still asking models to generate rich, open-ended language.

Implications For Trust, Knowledge, And Use

This has deep implications for how we trust and use AI.

We should treat language models less like oracles and more like cognitive instruments—powerful pattern amplifiers that must be embedded in human judgment.

A simple way to reframe trust:

- Trust the model’s form more than its facts. It is excellent at structure: drafting, rephrasing, outlining, generating perspectives.

- Be cautious with unverified specifics: names, numbers, citations, quotations, niche claims.

Here is a helpful comparison:

Use Case Type | AI Strength | Hallucination Risk | Recommended Stance |

|---|---|---|---|

Brainstorming ideas | High creativity and fluency | Low–medium | Use freely, then filter with judgment |

Drafting emails or essays | Strong structure and tone | Medium | Edit and fact-check key details |

Technical research summaries | Good at synthesis from sources | Medium–high | Verify against primary references |

Legal, medical, financial | Variable and high-stakes | High | Use only with expert oversight |

Rather than asking, “Can I trust AI?” a better question is, “For what, and under whose supervision?”

Practical Guidelines For Conscious Use

Working consciously with hallucination-prone systems means aligning our intellect and intuition with their strengths and limits.

1. Separate Exploration From Decision

Use AI liberally for exploration: mapping options, surfacing questions, generating angles. But insert a clear boundary before decision: anything consequential passes through human verification and, when needed, expert review.

2. Ask For Sources—And Check Them

When details matter, explicitly request references:

- “List sources and links you used.”

- “Cite specific papers or books.”

Then, open those sources yourself. If a citation cannot be found or does not say what the model claims, treat the answer as suspect.

3. Design Prompts That Invite Humility

You can encourage less confident guessing with prompts like:

- “If you are not sure, say so.”

- “Indicate your level of confidence and possible alternatives.”

This does not remove hallucinations, but it nudges the model toward epistemic honesty in style, which supports your own critical thinking.

4. Match Domain To Risk

Use models more freely in low-stakes, creative, or exploratory domains, and more cautiously in high-stakes, specialized ones. Part of conscious use is simply knowing where error is tolerable.

5. Keep A Human-in-the-Loop Ritual

Make a small ritual of review:

- Scan outputs for “too perfect” specifics.

- Cross-check 2–3 core claims.

- When something feels off, treat that intuition as a cue to investigate.

Over time, you train both the model (through feedback) and yourself (through pattern recognition).

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do AI models hallucinate even when they appear to be highly confident?

AI models hallucinate because they are built to predict the most statistically likely next word rather than verify factual truth. Because training rewards fluency and helpfulness, the model learns to prioritize linguistic coherence. This results in the generation of plausible-sounding details that are expressed with high confidence despite lacking grounding.

What causes AI hallucinations to increase when discussing niche or obscure subjects?

Hallucinations occur more frequently on niche topics because the training data is sparse or inconsistent in those areas. When an AI lacks clear patterns to follow, it compensates by blending related concepts and styles. This creates invented terms or explanations that fit the domain’s pattern but do not exist in reality.

Why are AI models programmed to provide answers rather than admitting uncertainty?

Most AI models are trained using objectives that reward providing helpful, complete responses to user prompts. Without specific penalties for fabrication, the model views generating a fluent, seemingly informed response as the most successful outcome. Consequently, the system prioritizes completing the text pattern over admitting it lacks the necessary information.

Can fine-tuning and safety training completely eliminate AI hallucinations?

Fine-tuning and safety training can reduce the frequency of errors but cannot eliminate them entirely. This is because the underlying architecture still functions as a probability-based text predictor. These methods nudge the model’s behavior, but they do not replace the core generative mechanism with a formal truth-checking or verification process.

How do AI hallucinations differ from human memory errors?

Human memory errors typically stem from faulty perception, emotional bias, or the decay of actual events. In contrast, AI hallucinations are purely structural side effects of pattern completion over text. The model synthesizes plausible linguistic structures based on language statistics, creating detailed fictions that are completely unanchored to any prior reality or experience.

Further Reading & Authoritative Sources

From thenoetik

- The Noetik — The Noetik explores the intersection of consciousness, philosophy, and technology. Its articles, such as ‘The Conscious Universe’ and ‘Calm on Demand Technology’, provide a philosophical framework for understanding reality and algorithmic influence, which complements the technical discussion of why AI models hallucinate.

Authoritative Sources

- Why does AI hallucinate, and can we prevent it? | — Authoritative enterprise-focused article detailing root technical causes of hallucinations in AI models (training data constraints, context window limits, model architecture) and mitigation strategies.