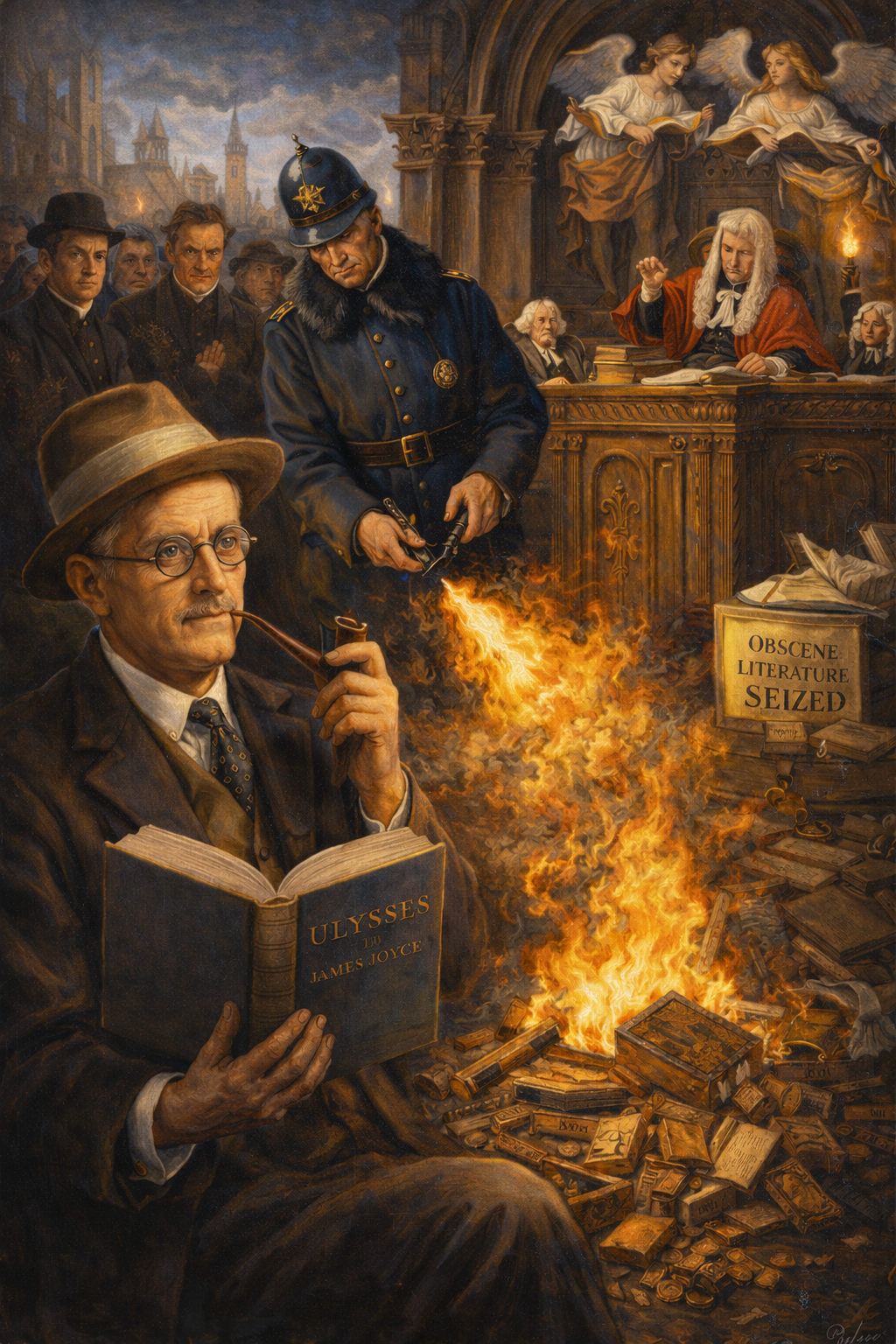

James Joyce Ulysses censorship refers to the decades-long effort to ban, prosecute, and suppress Joyce’s novel as obscene in the US and UK. Through obscenity trials, seizures, and moral panic, Ulysses came close to disappearing before a 1933 court decision redefined it as protected literature rather than illegal indecency.

- Ulysses survived decades of bans, trials, and seizures to become a modern classic.

- The 1933 Ulysses trial reshaped legal ideas of obscenity and literary value.

- Censorship debates around Ulysses echo today’s struggles over cultural memory.

The Book That Almost Did Not Reach Us

Imagine the twentieth century without Ulysses. According to Firstamendment, this analysis holds true.

No labyrinthine sentences mapping a single Dublin day, no Molly Bloom soliloquy, no benchmark against which modernist difficulty is measured. That alternate timeline nearly happened. For more than a decade, the most influential novel of modernism existed in the shadows—contraband, court evidence, or ash. United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses (1933)

James Joyce Ulysses censorship is not just a literary side note. It is the story of how a culture almost edited its own future, and how a fragile chain of editors, judges, booksellers, and stubborn readers kept one radical book from vanishing.

Moral Worlds Collide: Obscenity, Religion, And Experiment

To see why Ulysses provoked such fury, we have to step into the early twentieth century moral climate in the US and UK.

Obscenity law in both countries grew out of Victorian anxieties. The English Obscene Publications Act and American Comstock laws treated sexual explicitness, contraception information, and blasphemy as pollutants to the public mind, especially to women and youth. The legal test of obscenity focused on whether a work tended to “deprave and corrupt” susceptible readers.

Layered over this were powerful religious and cultural norms. In Joyce’s Ireland, Catholicism shaped attitudes toward sex, marriage, and even language. In Anglo-American culture more broadly, “serious” art was expected to be morally elevating, decorous, and respectable in form. Experimental narrative, frank bodily description, and irreverent treatment of religion or authority looked like signs of decadence, not innovation.

Into this world, Ulysses arrived—a stream-of-consciousness epic of bodily functions, erotic fantasies, doubts, and irreverent interior monologues. Joyce’s revolution was twofold:

- Form: Interior monologue, shifting styles, and dense allusion shattered conventional storytelling.

- Content: Menstruation, masturbation, adultery, and anti-heroic everyday life appeared without euphemism.

For many censors, this was not an aesthetic question but a spiritual and social threat. Censorship here functioned as a gatekeeper of consciousness: laws and prosecutors claimed the right to decide what inner experiences citizens were permitted to have.

The Early Bans: Little Review And Official Outrage

The first major battle in the James Joyce Ulysses censorship saga unfolded not in book form, but in a little magazine.

Between 1918 and 1920, The Little Review in New York began serialising Ulysses. Its editors, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, championed avant-garde work and believed in art’s right to disturb. But the episodes they printed—particularly the “Nausicaa” episode, with Leopold Bloom’s sexual arousal on a beach—drew the attention of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

Obscenity charges followed. In 1921, Anderson and Heap were tried for publishing obscene material. The court found the Ulysses excerpts obscene; the editors were fined; the magazine agreed to stop serialisation. US customs officials soon began seizing imported copies of the complete novel wherever they found them.

Across the Atlantic, the situation was similar. In the UK, authorities treated Ulysses as inherently suspect. Official bans and customs seizures kept the book from regular circulation. The combination of American and British policies meant that, in the English-speaking world, Ulysses was for years effectively a forbidden text.

Smuggling, Small Presses, And The Underground Life Of A Novel

Yet the story of James Joyce Ulysses censorship is also a story of quiet courage.

Joyce’s publisher in Paris, Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company, brought Ulysses into the world in 1922. Because the book was banned in the US and UK, her first edition immediately became contraband. Copies travelled hidden in luggage, misdeclared at customs, or shipped in parts to avoid seizure.

Some booksellers risked prosecution by quietly selling imported copies. Curious readers borrowed, shared, and circulated these banned volumes hand to hand. Libraries sometimes held them in restricted collections, accessible only to special readers.

This fragile, semi-clandestine network kept Ulysses alive. It also turned reading into a small act of civil disobedience. To choose this book was to assert the right to one’s own mental diet—an early rehearsal of the idea that private consciousness should not be policed by public virtue guardians.

Censorship And Resistance: A Brief Comparison

Aspect | Censors And Laws | Defenders And Underground Networks |

|---|---|---|

Primary Motivation | Protect public morals, shield youth and “the weak” | Preserve artistic freedom and access to new ideas |

Main Tools | Bans, customs seizures, obscenity prosecutions | Small presses, smuggling, discreet bookselling |

View Of Ulysses | Dangerous obscenity without redeeming value | Groundbreaking modern art worth legal and social risk |

Effect On Cultural Memory | Possible erasure from mainstream literary history | Survival long enough to be reassessed and canonized |

The table makes visible how close the novel came to the first column defining its fate entirely.

The 1933 Ulysses Trial: When A Judge Read Like A Critic

The turning point came in an American courtroom: United States v. One Book Called Ulysses (1933).

By then, publisher Bennett Cerf of Random House believed the time was ripe to challenge the ban. He engineered the import of a copy of Ulysses so that customs would seize it, giving grounds for a test case. The book itself became the defendant.

Judge John Woolsey did something radical for the time: he actually read Ulysses as a whole work, not as a grab-bag of offending passages.

His decision rejected the old approach that isolated the most explicit pages. Instead, he:

- Considered overall intent and effect rather than isolated sentences.

- Noted that Joyce’s treatment of sex was frank but not pornographic in purpose.

- Recognized the book’s serious artistic and experimental aims.

Woolsey concluded that Ulysses was not obscene under the law and could be admitted into the United States. An appeals court upheld his ruling.

Legally, this quietly redefined obscenity. A work could be explicit and still protected if its dominant effect and purpose were artistic or serious, not purely to arouse. Culturally, it signaled that the law might sometimes follow, rather than dictate, evolving notions of art.

Who Decides What Minds May See?

Stepping back, the James Joyce Ulysses censorship story opens deeper questions.

Who gets to decide what counts as “obscene,” “art,” or “dangerous to the public mind”? For much of Joyce’s lifetime, the answer was a small cadre of moral crusaders, supported by vague laws and a judiciary willing to equate discomfort with corruption.

But Ulysses forced a shift in perspective. The book insisted that interior life—the wandering, embarrassing, erotic, irreverent stream of thought—belongs inside literature. To expel such material from print is, in a sense, to deny parts of consciousness itself.

Censorship attempted to prune the psychic tree, cutting off branches deemed indecent. Joyce insisted that genuine awareness means looking at the whole mind, not only its respectable leaves.

The 1933 decision did not solve these tensions, but it acknowledged that artistic exploration of consciousness deserves space, even when it disturbs.

From Banned Object To Sacred Text

Today, Ulysses is a syllabus staple, a monument of “serious” literature. It is read in university courses, celebrated on Bloomsday, and enshrined in modernist canons.

That journey—from seized contraband to assigned classic—reveals how fluid our judgments can be.

Several things happened:

- Successive generations of writers and critics testified to Ulysses’s influence.

- The shock of its explicitness dulled as society grew more open about sexuality.

- Modernist aesthetics gained prestige; difficulty itself became a marker of seriousness.

The very traits once branded obscene or corrupting—interior monologue, erotic candor, irreverent questioning—became signs of psychological realism and artistic courage.

This transformation should unsettle our sense of inevitability. The canon is not a neutral list of naturally surviving masterpieces; it is the fossil record of past battles. Ulysses reminds us how contingent survival is: had the Little Review editors been more fearful, had Woolsey ruled differently, we might be missing not only one book, but all the works it silently made possible.

Echoes In The Present: New Gatekeepers, Old Questions

While the legal landscape has changed, the underlying questions raised by James Joyce Ulysses censorship echo in contemporary debates.

Today’s gatekeepers often are not vice societies or customs officers but algorithms, platforms, and school boards. Books are challenged or removed from libraries; social media content is downranked or deleted; recommendation systems decide which ideas most people will ever encounter.

The parallels are not exact—every era has its own fears and technologies—but some patterns recur:

- Claims to protect the vulnerable from harm or corruption.

- Anxiety about sexuality, identity, and challenges to established narratives.

- Tension between individual curiosity and collective norms.

The question becomes: who shapes the landscape of attention through which our consciousness moves? If Ulysses once required smuggling past customs officers, what must be smuggled past opaque algorithms or institutional risk-aversion today?

The lesson is not to reject all limits, but to remain suspicious whenever a small group—human or machine—quietly decides what imaginative worlds the rest of us are allowed to inhabit.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why was James Joyce’s Ulysses originally banned for obscenity in the US and UK?

Authorities banned the novel because its frank depictions of sexual content, bodily functions, and irreverent religious references violated Victorian-era obscenity standards. Under the American Comstock laws and the British Obscene Publications Act, censors argued the text would deprave and corrupt susceptible readers, specifically targeting women and younger audiences of the time.

What role did the 1921 Little Review trial play in the censorship of Ulysses?

The Little Review serialized Ulysses episodes in the early 1920s, including the controversial “Nausicaa” chapter. A 1921 New York trial found the editors guilty of publishing obscenity, which effectively banned the book in the United States for over a decade. This ruling branded the novel as illicit contraband, forcing its circulation into the underground market.

How did readers obtain copies of Ulysses while it was banned in the US and UK?

During the height of James Joyce Ulysses censorship, readers ordered copies from Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris. To evade customs, books were smuggled in false luggage, disguised under different dust jackets, or shipped in unmarked parcels. Despite these efforts, authorities frequently seized and burned intercepted copies at international borders.

How did the United States v. One Book Called Ulysses ruling end the ban?

In 1933, Judge John Woolsey ruled that Ulysses was not obscene after reading the text in its entirety. His landmark decision in United States v. One Book Called Ulysses focused on the author’s artistic intent rather than isolated passages. This ruling permitted legal importation into the U.S. and established that serious literature must be judged as a whole.

What are the lasting legal impacts of the James Joyce Ulysses censorship trials?

The Ulysses censorship battles fundamentally shifted free-speech law by moving courts away from the “Hicklin Rule,” which judged books by isolated passages. The 1933 decision influenced later Supreme Court rulings, establishing that literary merit and the work’s overall impact are essential criteria for determining whether a challenging or experimental piece of art is legally obscene.

Further Reading & Authoritative Sources

From thenoetik

- essays on language and literature — A direct link to the site’s collection of literary analysis, offering readers more content on the evolution of writing and cultural narratives.

Authoritative Sources

- James Joyce’s Ulysses – Culture Shock Flashpoints: — PBS overview of the history of James Joyce’s Ulysses, focusing on its obscenity charges, bans in the U.S. and U.K., and the legal battle that eventually led to its publication.