Silence, Inner Vision, And The Birth Of The Black Paintings

How deafness influenced Goya’s art can be traced in the way silence forced him inward, stripping away courtly noise and public flattery, and sharpening an inner vision that surfaced as brutally honest images of war, superstition, and despair, culminating in the Black Paintings that turned his own walls into a haunted interior landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Goya’s midlife deafness shifted him from public court painter to radical inner witness.

- Silence intensified his perception of violence, superstition, and psychological darkness.

- The Black Paintings transform private walls into a noetic map of inner experience.

Goya’s Silence As A Different Way Of Seeing

Goya did not simply lose a sense; he lost a social world. When illness left him permanently deaf in the mid‑1790s, the court’s music, gossip, and ritual vanished. What remained was a harsher soundscape: the remembered screams of executions, the mutter of superstition, the inner noise of fear.

In that enforced quiet, his art turns from flattery to exposure. To ask how deafness influenced Goya’s art is to ask how a human being paints when the outer world recedes and the inner world grows loud.

Before Silence: Court Painter In A Turbulent Spain

Before his illness, Francisco Goya rose from provincial origins in Aragón to become First Court Painter to Charles IV. His early works are full of daylight and public life: tapestry cartoons of festive gatherings, portraits of aristocrats, religious commissions glowing with Baroque inheritance.

Yet Spain was not calm. The Enlightenment pushed against monarchy and Church; the Inquisition still lingered; Napoleon’s ambitions would soon convulse the peninsula. Goya moved among ministers and nobles who adopted modern ideas while presiding over an ancient, often brutal order.

This is the outer stage on which his hearing collapses. His role depended on hearing: court ceremonies, proximity to power, the subtle cues of favor and danger. The political noise of Spain was the background hum of his career—until illness turned down the volume.

The Onset Of Deafness: Illness, Shock, And A New Kind Of Silence

Around 1792–1793, Goya suffered a severe, mysterious illness. He survived, but emerged with vertigo, weakness, and, crucially, profound deafness. Scholars debate the cause—lead poisoning, Ménière’s disease, syphilis—but the exact diagnosis adds less than the experiential fact: a man in midlife, at the height of social and professional visibility, suddenly unable to hear.

Silence, in his world, did not mean peace. There were no sign‑language communities around him, no cochlear implants, no disability studies. Deafness often meant isolation or being treated as unstable. The music of the court became memory; conversations dissolved into unreadable motions of lips; laughter was visible but not audible. Goya: The Deafness That Changed Art

This shock leaves traces in his letters, where he speaks of confusion and melancholy. More telling is what happens in his art: almost immediately after the illness, he begins a series of small, private paintings and drawings filled with nightmares, madhouses, and scenes of irrationality. The sound has gone out of the world; the irrational has stepped into the foreground.

From Outer Court To Inner World

Deafness pushed Goya to the margins of court life. He remained an official painter, but communication grew more difficult. Social ease gave way to observation from a distance. Instead of being fully inside the spectacle, he becomes its haunted witness.

The shift in his subject matter and tone is striking:

- From idealized festivities to satirical visions. The light of the early tapestry cartoons gives way to the acid fantasies of Los Caprichos (1799): grotesque faces, predatory monks, humans turning into beasts.

- From flattering portraits to psychological x‑rays. His likenesses of nobles and royals become less forgiving, more revealing of vanity, weakness, and anxiety.

- From smooth surfaces to restless mark‑making. His technique grows freer and darker; contrasts sharpen; shadows are not merely optical but moral and psychological.

Silence here is not a void; it is a pressure. Unable to rely on the stream of speech, Goya turns to what can still be trusted: vision, memory, imagination, and a new intensity of inner dialogue.

Darkness On The Walls: Reading Goya’s Late Works Through Deafness

The consequences of this inner turn appear across his dark period: Los Caprichos, The Disasters of War, and the Black Paintings he brushed directly onto the walls of his house outside Madrid.

Los Caprichos: When Reason Sleeps

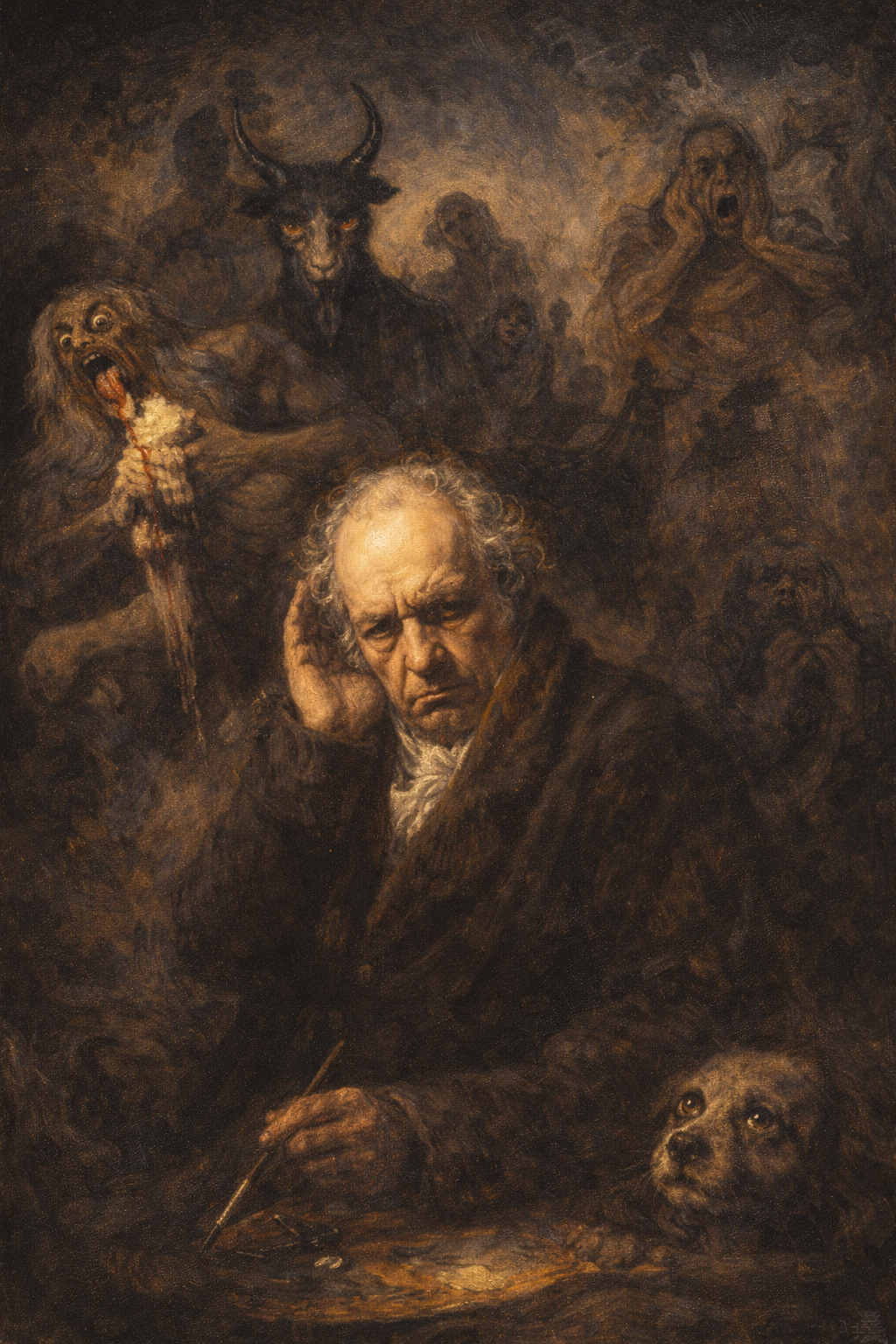

The famous plate from Los Caprichos—often titled The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters—shows a man slumped over a desk, besieged by owls and bats. It is an image of reason overwhelmed by the irrational.

In the wake of his deafness, Goya is that figure: cut off from ordinary conversation, yet wide awake to the cruelties and superstitions of his society. The monsters are not only Spain’s; they are the inner specters that visit when external chatter falls away and the mind must confront itself.

The Disasters Of War: Silent Screams

During the Peninsular War (1808–1814), Goya created the etching series The Disasters of War. These prints show executions, mutilations, famine—atrocities committed by both French and Spanish forces, with no heroic framing or clear moral comfort.

Here, deafness matters in a particular way. These are scenes defined by sound—gunshots, cries, chaos—yet on paper they are absolutely mute. Goya, who could not hear them, records them with an almost surgical clarity. The silence of the medium echoes the silence of his body.

The captions—“This is worse,” “I saw this”—carry the force of testimony. If he cannot hear, he can see, and seeing obligates him. The witness role becomes less social and more existential: he is responsible not to patrons, but to what his inner eye refuses to forget.

The Third Of May 1808: A Cry Without Sound

In The Third of May 1808, Goya paints Spanish rebels being executed by French soldiers. The central figure flings his arms wide, a human cross, his face a mask of terror and defiance.

The scene is visually loud: gunfire, shouts, prayers. But on canvas, and for the deaf painter, it is a frozen, soundless instant. This tension—between implied noise and painted silence—deepens the horror. The viewer almost strains to hear the shots that never come. Deafness becomes a metaphor within the work: the world’s violence continues, whether or not anyone is listening.

The Black Paintings: Saturn, Witches, And The Dog

In old age, living in the house known as the Quinta del Sordo (the House of the Deaf Man), Goya covered his walls with what we now call the Black Paintings (c. 1819–1823). These were not meant for public eyes. They are intimate, raw, and extraordinarily dark.

- Saturn Devouring His Son. The god’s eyes bulge; his mouth bites into the body he holds. There is no mythic distance, only cannibal panic. In the deaf painter’s house, the devouring is silent: no screams, only the endless present of the act. Time—Saturn—eats its children without explanation, as illness and history had devoured Goya’s own world.

- Witches’ Sabbath. A horned figure presides over a gathering of witches and haggard believers. Superstition, which Goya had mocked in Los Caprichos, now returns as an enclosing atmosphere. It is the noise of unreason, but shown in visual form—gestures, postures, faces—because sound is no longer his channel.

- The Dog. Perhaps the most enigmatic of all: a small dog’s head emerges from the bottom of a vast, empty field of ochre. Its gaze tilts upward, as if drowning or awaiting something that never arrives. No narrative explains it. The silence of the scene is almost metaphysical, as if Goya’s own condition has been distilled into a single mute consciousness beneath an indifferent expanse.

Painted directly on his walls, these works turn architecture into psyche. The house becomes an externalized inner ear, not receiving sound but echoing images formed in solitude.

How Deafness Reshaped Perception, Imagination, And Noetic Insight

Deafness did not give Goya genius; he was already an accomplished painter. But it altered the direction and intensity of his intelligence. One channel closed; others amplified.

- Heightened visual attention. Cut off from speech, he read faces, bodies, and social scenes more acutely. The twist of a mouth, the slump of a peasant, the theatricality of a general—these become primary data.

- Deepened memory and imagination. Experiences could no longer be refreshed through casual retelling and conversation. Instead, they recirculated inside, combining into composite visions: witches’ gatherings, nightmare feasts, archetypes of cruelty.

- Inner dialogue as primary theater. Silence turned inwardness from option to necessity. His art becomes the transcript of a mind thinking, fearing, and questioning in images.

A noetic reading—seeing knowledge as the union of intellect and intuition—illuminates his transformation. Goya’s late work does not merely illustrate ideas; it thinks in paint. The Black Paintings, especially, feel less like messages to an audience and more like the mind’s attempts to understand itself under pressure.

A Brief Comparison Of Goya’s Pre‑ And Post‑Deafness Art

| Aspect | Before Deafness (Court Period) | After Deafness (Dark Period) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Court portraitist, decorator of royal residences | Witness of war, critic of superstition, private visionary |

| Dominant Tone | Festive, flattering, luminous | Tragic, satirical, nightmarish, introspective |

| Typical Subjects | Royals, aristocracy, religious scenes, pastoral life | Executions, witches, monsters, anonymous victims, haunted interiors |

| Use Of Light And Color | Clear daylight, rich fabrics, balanced compositions | Stark contrasts, muddy earth tones, engulfing darkness |

| Intended Audience | Court, Church, public commissions | Often private or unpublished in his lifetime (prints, wall murals) |

Seen this way, how deafness influenced Goya’s art is not a minor biographical footnote; it is a hinge that swings his work from the outer theater of power to the inner theater of consciousness.

Modern Parallels: Noise, Withdrawal, And Creative Depth

Goya’s “productive silence” speaks to our own age of constant notification. We flood ourselves with noise he had stripped away by force. His trajectory asks a simple question: what might we see if our everyday soundscape were interrupted?

This does not mean romanticizing disability or pretending that his suffering was a gift. Rather, it suggests that when one mode of engagement collapses, others can deepen. Solitude, when it is not chosen, can still become a site of perception rather than only of emptiness.

The lesson is not to imitate his extremity, but to notice how rarely we allow any channel of input to fall silent. Goya shows what happens when the outer court recedes: the inner court—of memory, intuition, moral imagination—steps forward, bearing images we might otherwise refuse to see.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary differences between Goya’s court portraits and his post-illness works?

Goya’s early court works prioritized bright palettes, decorative rococo styles, and flattering aristocratic aesthetics. Following his mid-1790s deafness, his style transitioned into darker, more expressive modes characterized by muddy tones, heavy impasto, and grotesque figures that replaced traditional courtly elegance with raw psychological depth, social critique, and intense visual honesty.

What specific techniques in the Black Paintings reflect Goya’s experience of deafness?

Goya utilized shadow-saturated palettes and claustrophobic, compressed spaces to mimic the sensory isolation of silence. By dissolving backgrounds into dark voids, he forced the viewer to focus on exaggerated physical gestures and mute facial expressions, effectively translating the absence of sound into a haunting, visual interiority that defined his later career at Quinta del Sordo.

How did silence influence Goya’s depiction of violence in “The Disasters of War”?

Silence transformed Goya’s perception of conflict from heroic narrative into intimate, sensory horror. Without the auditory distractions of battle, he focused on the physical mechanics of suffering. His etchings emphasize the brutalized human body and moral despair, stripping away patriotic glory to expose the raw, echoing trauma of the Peninsular War through an unblinking lens.

In what way did Goya’s loss of hearing impact his portrayal of Spanish superstition?

Deprived of social conversation, Goya focused on the visual irrationality of the Inquisition and folk witchcraft. His deafness amplified his perception of the “monsters” created by a lack of reason, leading to art where nightmares and reality blur. Figures like witches and friars became symbols of a society governed by silent, terrifying ignorance and communal panic.

When did Goya become deaf and how did it affect his professional status?

Goya lost his hearing in 1793 following a severe, undiagnosed illness while traveling in Andalusia. This permanent sensory loss ended his participation in royal court social life and music. While he remained First Court Painter, the resulting isolation drove him toward independent “capricho” works, allowing him to bypass official censors and explore darker, private themes.

Further Reading & Authoritative Sources

Authoritative Sources

- Deafness and mentality in Francisco Goya’s paintin — Peer‑reviewed medical humanities article analyzing how the illness that caused Goya’s deafness divided his career into two periods and how post‑illness deafness intensified the gloom, satire, and psychological depth of his art.

- “Black Paintings” in the Quinta del Sordo (1820–18 — Authoritative art‑historical entry that directly links Goya’s permanent deafness after serious illness to the changing character and dark, fantastical imagery of his late Black Paintings executed in the ‘House of the Deaf Man.’

- Medical deafness or the madness of war: Goya’s mot — Scholarly essay from a medical humanities journal that examines how Goya’s physical deafness, psychological isolation, and experiences of war together shaped the macabre themes and style of his late Black Paintings.