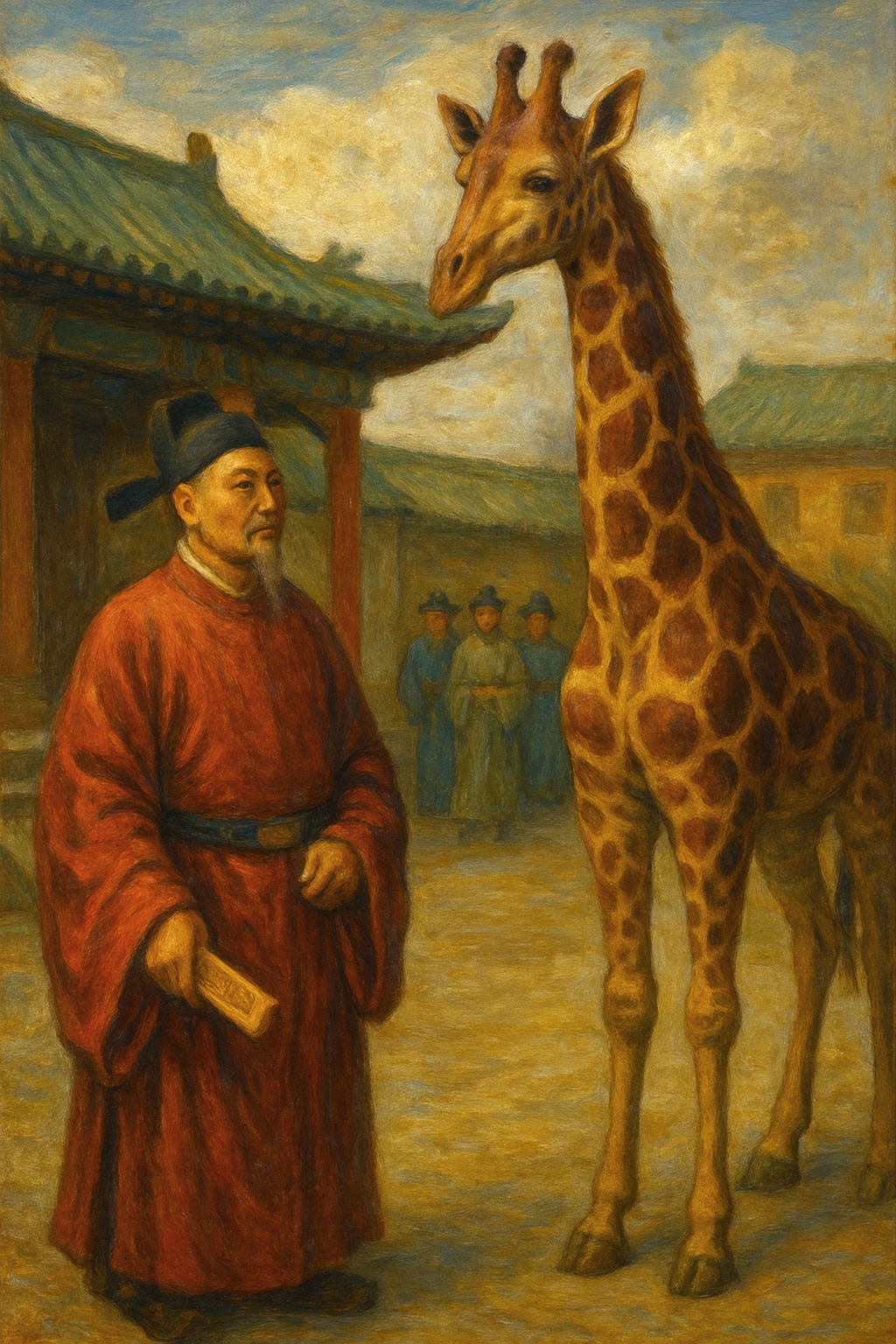

The arrival of a giraffe in 1414—named a qilin by the Yongle court—illuminates how Ming dynasty diplomacy turned exotic gifts into instruments of legitimacy, tribute, and maritime influence.

Who was Zheng He and why the treasure voyages mattered

Zheng He (1371–1433) led the Ming treasure voyages that projected imperial power across the Indian Ocean. Under the Yongle Emperor, Zheng He’s voyages combined statecraft, commerce, and spectacle: they secured tributary ties, protected trade, and staged grand diplomatic performances using gifts and animals. The scale and choreography of these missions — the treasure fleet (bao chuan) — were central to Ming dynasty diplomacy and the maritime Silk Road Zheng He navigated.

Transitioning from local politics to oceanic theater, Zheng He’s expeditions show how early modern diplomacy relied as much on spectacle as it did on negotiation.

Expanding the point: the treasure fleet was not merely a trading enterprise but a complex instrument of policy. Each ship, envoy, and cargo item had a role in signaling Ming authority, establishing long-term market access, and creating reciprocal obligations. Ming dynasty diplomacy, in this sense, was logistical—requiring provisioning, mapping, local intelligence—and performative—requiring ceremonies, inscriptions, and displays of wealth.

Case study (brief): The Yongle Emperor’s decision to send seven major expeditions between 1405 and 1433 demonstrates the state’s sustained commitment to maritime projection. These voyages involved thousands of men, hundreds of ships, and deliberate protocols for engagement: arrival ceremonies, tribute exchanges, and formal investitures that reinforced a Sino-centric world order.

The giraffe’s provenance and maritime routes

The giraffe that reached Nanjing likely had biological origins on the East African coast (the Swahili world) and travelled through Indian Ocean networks of Malindi, Arabia, and South Asia before arriving as a diplomatic gift. These routes illustrate the complexity of long-distance exchange: merchants, local rulers, and brokers all shaped provenance claims. Thus the giraffe’s journey is a small case study in how Ming dynasty diplomacy depended on layered, multilingual trade circuits.

Detailed example: Swahili port-states such as Malindi had established links with Chinese mariners; Malindi rulers are documented as allies of Zheng He who provided guides and gifts. This chokepoint in the exchange network is crucial: goods and animals from the African interior were consolidated, cared for on long voyages, and then presented as sovereign-signifying tribute in Asian courts.

Biological and documentary evidence together point to a multi-stage itinerary: capture/procurement in sub-Saharan East Africa; transport to coastal bazaars; purchase or diplomatic transfer at ports like Malindi; onward carriage by Arab, Indian, or indigenous Swahili mariners; reception by Chinese emissaries and eventual presentation at the Yongle court. Each stage left room for interpretations and re-labelings that shaped the object’s political value.

The “unicorn” moment — naming, symbolism, and policy

When court recorders called the giraffe a qilin (“unicorn”), the act was symbolic translation rather than zoological error. Calling the animal a qilin performed three diplomatic functions:

- Interpretation: It made the unfamiliar intelligible within Chinese cosmology.

- Legitimization: It turned an exotic gift into a sign of heavenly favor for the Yongle Emperor.

- Containment: It domesticated difference, converting potential uncertainty into usable political theology.

This rhetorical move shows how Ming dynasty diplomacy converted objects into narratives that reinforced an imperial world order.

Expert insight: As Edward L. Dreyer has emphasized in his synthesis of Zheng He’s voyages, the court’s practice of renaming foreign objects and peoples was a deliberate exercise in narrative control. Dreyer argues that this process made foreignness manageable: by mapping unfamiliar things onto known categories, the court could incorporate them into imperial ritual and historiography.

Comparative note: Similar practices appear in other early modern polities. Ottoman and Safavid courts also reframed foreign emissaries and gifts to fit domestic protocols, but the Ming emphasis on cosmological legitimization—interpretive naming like “qilin”—is a distinctive expression of East Asian political theology.

Diplomatic consequences of the giraffe

The giraffe’s arrival produced concrete effects on foreign relations:

- It bolstered Yongle’s prestige and claims to the Mandate of Heaven.

- It reinforced the tribute system Ming dynasty channels used to structure Sino-centric ties.

- It stimulated further tribute missions and exotic gift exchanges, increasing maritime traffic and cultural flows.

In short, a single exotic animal became both theater and policy — an emblem of how material culture influenced statecraft.

Case study follow-up: After the giraffe’s presentation, the Yongle court recorded subsequent increases in requests to exchange gifts and enter tributary relations. Local rulers in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, having observed the effective publicity value of such exchanges, were more likely to seek formal ties—thus creating a multiplier effect that shaped the geopolitics of the region.

Practical application: For historians and diplomats today, this episode underscores the multiplier effect of high-visibility diplomacy: a single spectacle, properly staged and recorded, can reshape patterns of expectation and engagement among a wide network of polities.

Zheng He’s voyages and related practices (LSI: giraffe diplomacy, tribute system)

Zheng He’s voyages routinely carried rarities — from ivory and pearls to animals — that functioned as diplomatic gifts. Giraffe diplomacy sat alongside other practices (horse and elephant gifts, envoy exchanges) that together formed a repertoire of influence along the maritime Silk Road.

Detailed inventory example: Surviving accounts list not only large animals but also technological gifts (e.g., clocks, textiles) and ritual objects (e.g., ceremonial seals). These were carefully selected to appeal to the receiving court’s values—horses for military courts, silk and porcelain for commercial elites, and exotic fauna for cosmological courts like Ming China.

Step-by-step guide — how a tribute gift was processed under Ming dynasty diplomacy:

- Arrival and quarantine: Exotic animals and goods were disembarked and tended in special compounds to ensure their health.

- Official inspection: Court officials and appointed naturalists/keepers examined the items and compiled descriptive records.

- Naming and classification: Scribes framed the object’s meaning by assigning it to known cosmological or administrative categories (e.g., “qilin”).

- Ritual presentation: The object was paraded before the emperor and used in symbolic ceremonies to publicly link the gift to imperial favor.

- Archival recording: The event and documents were entered into the Ming Shilu and other court registers, which amplified the event through bureaucratic memory.

- Redistribution or display: Gifts might be housed in imperial menageries, redistributed to officials, or used in future diplomatic exchanges.

This routinized pathway is central to understanding how Ming dynasty diplomacy transformed things into political capital.

Reading the episode: sources, images, and further context

Primary eyewitness accounts (Ma Huan, Fei Xin) and Ming court records (Ming Shilu) provide the documentary spine for this episode; modern syntheses by Dreyer and Levathes offer archival context and interpretation. For accessible background on Zheng He and his voyages see major reference works and scholarly monographs [1][2].

Suggested visuals: a route map linking Swahili ports to Fujian and Nanjing, a timeline (1405–1433), and archival illustrations of the giraffe-as-qilin.

Expert quote (paraphrase with emphasis): Scholars often note that the power of Ming dynasty diplomacy lay less in coercion and more in the court’s ability to shape perceptions. As Louise Levathes writes in popular synthesis, the spectacles of the treasure fleet created an image of Chinese reach that resonated long after the ships sailed.

Reflection: what Ming dynasty diplomacy teaches us today

The giraffe episode reminds us diplomacy is storytelling as much as negotiation. Objects arrive; then humans decide what they mean. In this case, a biological curiosity was refitted into a cosmic story that strengthened imperial authority and reshaped international optics.

How do we read modern diplomatic theater differently when we remember that material tokens often carry manufactured meaning?

Practical implications for contemporary diplomacy:

- Soft power through cultural artifacts: States can create durable narratives by staging cultural exchanges in ways that appeal to domestic and foreign audiences.

- Information management: As in the Ming court’s archival practices, controlling the record—photos, press releases, curated displays—remains essential.

- Local intermediaries matter: The giraffe’s journey shows that third-party brokers and local rulers are decisive in shaping the political content of exchanges.

Future trends and predictions: Looking forward, the logic behind the giraffe moment persists. Digital diplomacy will substitute for some physical spectacles, but the appetite for visual, disruptive, and symbolic acts of statecraft will remain. Museums, traveling exhibitions, and state-sponsored cultural exchanges will continue to serve as arenas where nations seek reputational leverage—now with social media amplifying any spectacle globally.

Sources & suggested further reading

- Primary: Ma Huan, Yingya Shenglan; Fei Xin, Xingcha Shenglan; Ming Shilu (Veritable Records).

- Secondary: Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty; Louise Levathes, When China Ruled the Seas.

Authoritative overviews and reference entries provide concise entry points for readers [1][2].

Citations

[1] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Zheng He (reference article)

[2] Cambridge University Press / Scholarly monographs on Zheng He and Ming maritime history