Do mountains move? Standing beneath a granite ridge, the question feels almost absurd. However, mountains are not inert: they rise, slump, slide, and flex. This essay explains how plate tectonics and the processes of faulting and folding in mountains shape ranges over seconds to millions of years, while also touching on cultural myths and modern measurement methods.

Key Takeaways

- Mountains move by many processes: faulting, folding, thrusting, uplift, erosion, and isostatic rebound.

- Faulting and folding in mountains are central to mountain formation and to understanding hazards such as earthquakes and landslides.

- We measure motion with GPS, InSAR, seismology, and cosmogenic dating to detect millimeters-per-year uplift and sudden meter-scale changes.

- Cultural myths about “moving mountains” reflect human attempts to make sense of observable landscape change.

Faulting and Folding in Mountains: Do Mountains Move?

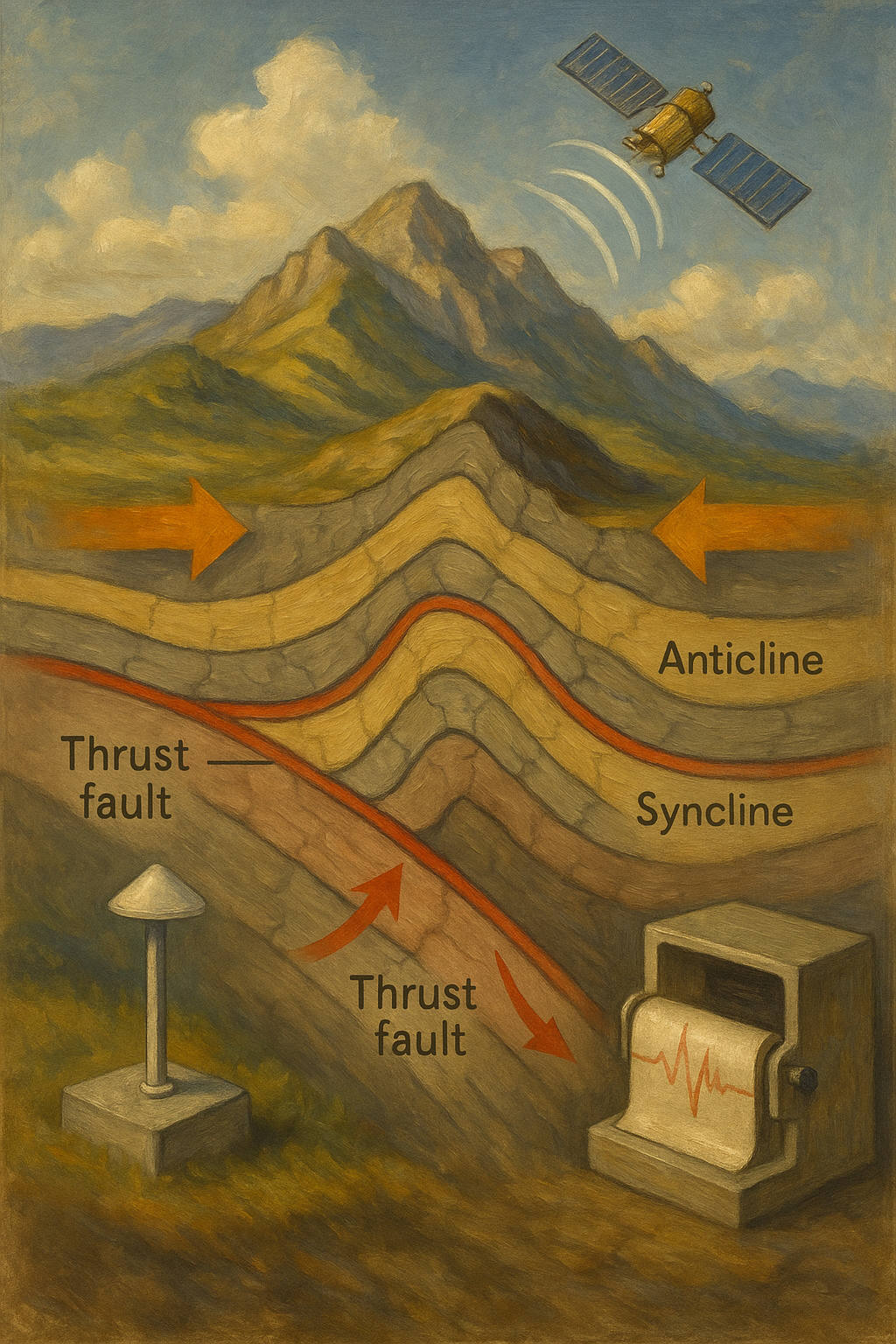

Yes. In fact, the phrase “faulting and folding in mountains” names two of the most important ways ranges change. Faults break the crust and allow blocks to shift suddenly or slowly, whereas folds bend rock layers under compression. Together, these processes both build and deform mountain belts. For example, thrust faults can stack slices of crust and, therefore, significantly increase elevation, while folding thickens crust more gradually.

Moreover, faulting and folding interact with surface processes: erosion, glacier retreat, and river incision. Consequently, a mountain that appears fixed will, over time, be rewritten by both tectonic forces and surface change.

To visualize the distinction: imagine a rug pushed from one end. The rug will crumple into folds (analogous to folding). If the rug tears and a piece slides, that’s like a fault. In real mountain belts, folding and faulting often co-occur and can migrate across a belt through time.

How Do Mountains Form? Plate Tectonics and Mountain Formation

At the largest scale, mountain formation is a consequence of plate tectonics. When plates converge, the crust shortens and thickens through folding and faulting. Key terms and processes include:

- Plate tectonics and mountains: convergent plate boundaries—especially continental collisions—generate the most dramatic ranges (e.g., the Himalaya).

- Orogeny meaning: an orogeny is the mountain-building event produced by tectonic collision, thrusting, and folding.

- Thrusting and stacking: crustal slices (thrust sheets) pile up, producing nappes and high plateaus.

In short, plate motions drive uplift, and while uplift rates are often measured in millimeters per year, over geologic timeframes they produce kilometers of relief.

Historical note: recognition of folding and faulting as drivers of mountain building dates back to 19th-century geologists such as Charles Lyell and later to structural geologists who mapped fold-thrust belts in the European Alps. Understanding evolved from simple descriptive mapping to plate-tectonic synthesis in the mid-20th century, when the mechanistic role of lithospheric plates became clear.

How Fast Do Mountains Move? Uplift, Erosion, and Displacement

Movement occurs on many timescales:

- Immediate (seconds to minutes): earthquakes and rock avalanches can change slopes and coasts overnight. For example, the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake produced multi-meter coastal uplift in places.

- Human memory (years to centuries): landslides, road offsets, and changes in drainage are easily observed on human timescales.

- Geologic time (thousands to millions of years): orogeny, long-term uplift, and erosion reshape ranges and drive migration of topography.

Typical uplift rates for active ranges are millimeters to centimeters per year. For instance, many parts of the central Himalaya uplift at roughly 5–10 mm/yr, while central Alpine zones often show ~1–3 mm/yr uplift. Yet sudden fault slip or massive slope failure can produce meters of change in an instant.

Case study: Himalayan front

In the Himalaya, active thrust faults like the Main Himalayan Thrust accommodate India–Eurasia convergence. Geodetic networks reveal episodic slip on these faults during large earthquakes combined with steady interseismic strain accumulation. Rivers incise rapidly in the same area, so erosion and uplift are coupled: as the range is pushed up by faulting and folding in mountains, rivers cut downward, creating steep relief and frequent slope failures.

Tools: Measuring Faulting and Folding in Mountains (GPS, InSAR, Seismology)

We can quantify how mountains move using precise instruments:

- GPS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems): continuous stations record mm-scale vertical and horizontal motion over years.

- InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar): satellites map surface deformation with millimeter precision across wide areas; especially useful after earthquakes or for slow landslides.

- Seismology: earthquake records reveal fault slip, rupture directivity, and energy release.

- Cosmogenic nuclide dating and radiometric dating: estimate exposure ages and erosion histories, helping infer long-term uplift.

These tools together let scientists read motion from minutes to millennia and connect faulting and folding in mountains to measurable signals.

Practical integration example:

A modern field study may combine aerial LiDAR, InSAR time-series, and GPS to map an active fold that shows subtle coseismic uplift. LiDAR reveals abandoned river terraces offset by folding, InSAR tracks current slow deformation, and trenching across a fold uncovers stratigraphic evidence of past earthquakes. Together, these lines of evidence quantify recurrence intervals and slip amounts.

Expert insight: Many structural geologists emphasize that no single method suffices. “You need a multi-disciplinary approach—remote sensing, field mapping, and paleoseismology—to fully understand active fold and fault behavior in mountains,” says an experienced researcher working on active orogens.

Human Stakes: Faulting and Folding in Mountains, Hazards and Resources

Because faulting and folding in mountains creates relief and instability, there are practical implications:

- Hazards: Earthquakes, landslides, and rock avalanches threaten communities and infrastructure. Therefore, mapping active folds and faults is critical for hazard mitigation.

- Infrastructure and planning: Roads, pipelines, and dams must account for uplift, slope stability, and seismic risk.

- Water and resources: Mountain uplift concentrates minerals and builds glaciers and aquifers (“water towers”), so changes affect water supply and mining access.

Practical application: engineering design

Engineers use geological maps of fold-thrust belts to site tunnels and roads. Design standards for mountain infrastructure increasingly integrate probabilistic seismic hazard assessments that account for both background seismicity and potential surface rupture along mapped faults.

Comparative point: areas dominated by folding (broad anticlines and synclines) tend to have long-term, distributed deformation, while areas dominated by large active faults may experience localized, high-magnitude displacement. Both regimes require tailored planning.

Resource example: the Zagros fold-thrust belt in Iran concentrates petroleum in anticlines. Recognition of folding patterns directly informs exploration strategies and economic decisions.

Myths and Meaning: Cultural Stories of Moving Mountains

Stories about moving mountains appear worldwide. While they are not scientific records, these myths often encode observations about dramatic landscape change:

- Greek: Atlas as a metaphor for immense loads and geologic strain.

- Hindu: Puranic tales of gods reshaping ranges, reflecting awareness of dynamic landscapes.

- Indigenous narratives: Many communities interpret dramatic events—landslides, river diversion, or coastline change—as memory embedded in story.

Thus, myth and science complement each other: one offers cultural resonance, the other measurable explanation.

Anthropological note: oral histories sometimes align with geologic events such as tsunami inundation or landslides. Researchers increasingly work with local communities to correlate mythic descriptions with paleoseismic or geomorphic evidence.

Further Reading and Authoritative Sources

For reliable, in-depth information, consult authoritative sources such as the United States Geological Survey and NASA Earth Observatory. In addition, peer-reviewed review articles in journals like Nature Geoscience synthesize uplift and erosion interactions.

- USGS (plate tectonics and mountain building) provides accessible overviews of mountain processes.

- NASA Earth Observatory and mission pages detail remote-sensing tools such as InSAR used to measure deformation.

(External links in the sidebar point to these resources.)

Reflection: Permanence, Impermanence, and Stewardship

Mountains teach humility: what looks permanent changes, slowly or suddenly. Therefore, noticing a shifted trail, a new cliff, or a changing river is not only a practical observation but also an invitation to reflect on time, care, and responsibility. Which landscape has shaped how you imagine permanence and change?

Practical Guide: How to Assess Faulting and Folding in Your Area (Step-by-Step)

- Gather maps and satellite imagery: begin with geological maps, high-resolution topography (LiDAR if available), and satellite imagery to identify linear scarps, warped terraces, or aligned springs.

- Field reconnaissance: look for tilted strata, folded beds, exposed thrusts, and displaced river terraces. Photograph and measure bedding orientations where possible.

- Install or consult GPS/InSAR data: check whether existing GNSS stations or InSAR time-series indicate active deformation.

- Paleoseismic trenching (if permitted and appropriate): excavate across suspected faults to reveal past rupture events and date them using radiocarbon or luminescence methods.

- Hazard assessment: combine the geological and geodetic evidence into a risk map indicating likely zones of rupture, landslides, and secondary hazards such as damming of rivers.

- Communicate findings: share results with local authorities, planners, and communities to inform land use and emergency planning.

This stepwise approach links observation to action and helps communities live more safely in active mountain regions.

Comparative Analysis: Folding vs Faulting — Which Is More Dangerous?

- Faulting: produces sudden displacement during earthquakes. Surface rupture and strong shaking make faults primary hazards near active strands.

- Folding: often produces subtle deformation across wider areas; it may not produce dramatic single events but can control slope stability and long-term drainage changes.

In many settings, the combination of folding and faulting creates the highest hazard: uplifted, steepened slopes are prone to landslides triggered by seismic shaking.

Future Trends and Predictions

Looking ahead, several trends will advance our understanding of faulting and folding in mountains:

- Expanded satellite constellations (more frequent InSAR revisits) will allow near-real-time monitoring of slow deformation and post-seismic relaxation.

- Machine learning and automated change detection will accelerate mapping of active geomorphic features from large datasets.

- Integrating climate models with geomorphic and tectonic models will clarify how changes in precipitation and glacial mass affect slope stability and uplift (e.g., accelerated erosion may change stress on faults).

- Community science and low-cost GNSS sensors will democratize monitoring, enabling local groups to contribute valuable observations.

These advances mean we will better predict where and how mountains will change and translate that knowledge into safer planning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Do mountains actually move, and if so, how fast?

A: Yes. Mountains move through uplift at rates typically measured in millimeters to centimeters per year (e.g., parts of the Himalaya ~5–10 mm/yr) and by sudden events—earthquakes and landslides—that can shift meters overnight.

Q: What is the difference between folding and faulting?

A: Folding bends rock layers into anticlines and synclines under compression, while faulting breaks rocks and allows blocks to slide past each other along discrete surfaces. Both processes commonly occur together in orogenic belts.

Q: How do scientists measure these motions?

A: Primary tools include continuous GPS networks, InSAR satellite imagery, seismology for earthquake rupture, and cosmogenic nuclide dating for long-term uplift and erosion histories.

Q: Can myths about moving mountains be trusted as evidence?

A: Myths are cultural records that may encode observations of past events (e.g., large landslides). They complement scientific evidence but are not substitutes for geologic data.

Q: How should communities respond to mountain movement hazards?

A: Use hazard maps, monitor active faults and unstable slopes, restrict development in high-risk zones, and design infrastructure to accommodate likely deformation and seismic loading.

Q: Are there famous places where “faulting and folding in mountains” is especially visible?

A: Yes. The Zagros (Iran) and the Canadian Rockies show classic fold-thrust belts; the Himalaya demonstrates active large-scale thrusting; the Andes display folding on the volcanic arc; and tectonically active coastal ranges such as New Zealand’s Southern Alps show rapid uplift and complex fault-fold interactions.

Q: What are simple signs of active folding or faulting in the landscape?

A: Look for warped river terraces, aligned springs, sudden cliff faces, linear valleys, scarps, and tilted or overturned strata exposed in road cuts or stream banks.

Final thought

Faulting and folding in mountains are processes written over different tempos of time: sudden jerks and patient bends. Understanding them requires both precise instruments and grounded field observation — and their study connects profoundly to human safety, resource use, and cultural meaning.