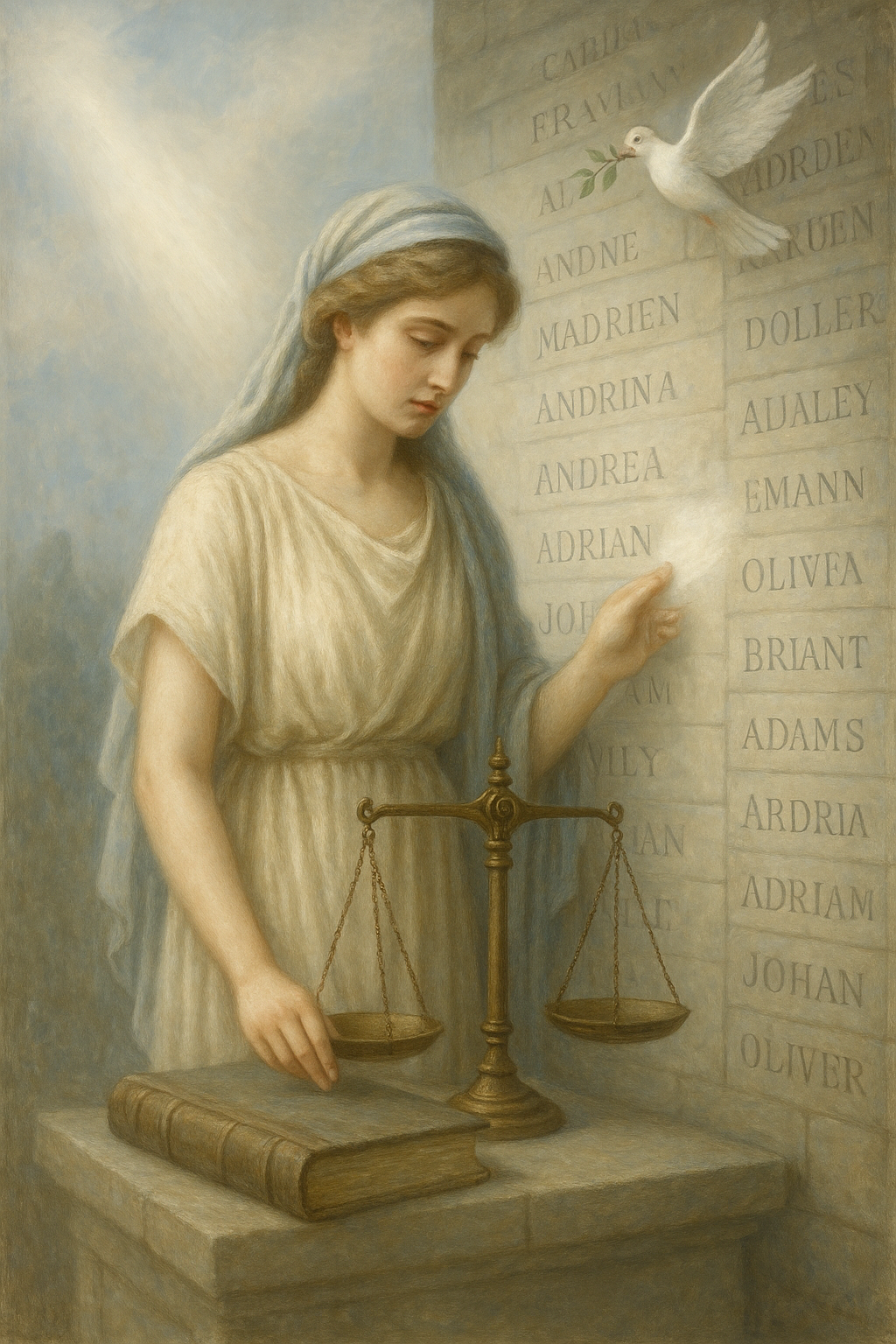

Imagine a town that carves the names of every wrongdoer into a public wall. The goal is to remember history and prevent repeating harm. Yet for a survivor, living beside her perpetrator’s name is a daily trauma. She asks for it to be removed. Civic leaders refuse, fearing that erasing the past betrays justice. This tension lies at the heart of the ethics of forgetting.

This short guide helps individuals, communities, and institutions decide when to let go ethically and how to do so responsibly — from personal grief to digital data and transitional justice.

Ethics of Forgetting

- The “ethics of forgetting” weighs memory as justice against memory as burden: choose forgetting when it reduces present harm, respects consent, and does not erase accountability.

- Intentional forgetting differs from repression: it is a conscious, often negotiated act (personal, therapeutic, legal, or social).

- Use practical criteria (justice, harm reduction, consent, public interest, power dynamics, reversibility) to decide whether and how to let go.

- In the digital realm, the right to be forgotten (e.g., GDPR Article 17) shows how legal frameworks balance privacy and public interest (GDPR text).

Understanding the Ethics of Forgetting: Forgetting, Forgiving, Repressing

To act ethically, we must clarify terms often used interchangeably.

- Forgetting: natural decay or intentional removal/non-retrieval of memory or records.

- Forgiving: a moral choice to release resentment; it can coexist with preserved memory (see forgiveness and forgetting).

- Repressing: typically an unconscious defense (controversial in modern psychology); different from deliberate, consented forgetting.

- Choosing to forget: intentional, often negotiated steps (e.g., redaction, time-limited amnesty, data deletion).

These distinctions matter because the ethics of forgetting depends on agency and transparency. When an institution chooses to obscure its past without consultation, that is ethically different from a survivor requesting redaction to protect well-being.

The Science of Memory and the Ethics of Forgetting

Neuroscience and psychology frame what is possible and ethical for memory work.

- Our brains forget adaptively (Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve): forgetting frees cognitive resources for new learning.

- Intentional suppression (the “think/no-think” paradigm) shows people can dampen recall; related neuroscience implicates prefrontal control over hippocampal retrieval.

- Trauma produces persistent, intrusive memories (PTSD); ethical therapeutic approaches aim to reduce emotional charge rather than promise erasure.

Recent work on memory reconsolidation suggests that while complete erasure is not reliably achievable, the intensity and accessibility of memories can be altered. Clinicians and ethicists emphasize that interventions aimed at reducing suffering should respect identity and truth: altering memory too aggressively can disrupt a person’s narrative continuity.

For accessible background on philosophical and scientific perspectives, see the Stanford Encyclopedia’s entry on forgetting and memory and summaries of motivated-forgetting research (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; selected neuroscience reviews at NCBI).

An Ethical Framework: 7 Criteria for the Ethics of Forgetting

Use the following criteria as a checklist when weighing a forgetting decision:

- Justice & accountability: Will forgetting block redress or hide wrongdoing? If yes, preserve memory.

- Harm reduction: Does retention cause ongoing, serious harm to living persons? If yes, redaction or removal can be justified.

- Autonomy & consent: Do affected parties (especially victims) consent to forgetting? Voluntary forgetting carries more moral weight.

- Public interest & truth: Does the memory serve civic knowledge, safety, or historical truth that the public requires?

- Temporal distance & restitution: Have reparations, apologies, or legal remedies occurred? Structured forgetting is more legitimate after these.

- Equity & power: Who benefits? If forgetting shields the powerful, it is ethically suspect.

- Feasibility & reversibility: Is erasure technically feasible and reversible? Irreversible deletion raises higher stakes.

Apply these holistically: no single criterion decides every case. The ethics of forgetting is a balancing act; context and proportionality matter.

Real-World Scenarios — How to Let Go Responsibly

Personal relationships: when to let go of someone

If a relationship causes ongoing harm and accountability or repair is absent, ending it (and choosing to stop ruminating) may be both psychologically healthy and ethically defensible. Conversely, forgetting without accountability risks enabling repeat harm.

Practical example: a person leaves an abusive partnership, asks friends and social networks to stop sharing photos or stories that expose them to the abuser. Respecting that request is an act of moral solidarity that reduces harm without rewriting the past.

Trauma therapy: therapeutic forgetting and processing

Therapies such as CBT or EMDR focus on integrating traumatic memories so they lose their intrusive power — a form of letting go that preserves truth while reducing harm. Clinicians should avoid promising literal memory erasure.

Case study: a veteran with PTSD learns through therapy to reconceptualize traumatic episodes as parts of a broader life story rather than defining frames. The memory remains, but it no longer dictates daily functioning.

Digital life: right to be forgotten and data deletion services

Under EU law, the GDPR provides mechanisms for erasure requests. Platforms must balance removal against public interest (newsworthiness). Because cached copies and backups often persist, digital forgetting is rarely absolute; use professional reputation-repair services only with clear expectations and documented consent (GDPR text).

Legal case: Google v. Spain (C‑131/12) established an individual’s ability to request delisting of search results that are “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant.” This is a concrete illustration of how legal rules operationalize the ethics of forgetting in the online sphere.

Transitional justice: memory vs. negotiated forgetting

Truth commissions sometimes combine public testimony with conditional amnesties to stabilize peace. Ethical forgetting in these contexts depends on acknowledgment, reparations, and victims’ voices being central.

Historical context: Spain’s “pact of forgetting” after Franco exemplifies a political choice to prioritize stability over prosecutions, a decision that remains contested decades later. By contrast, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission foregrounded public truth-telling paired with conditional amnesty, centering victims’ testimony and attempts at restorative justice.

Comparative note: In Rwanda, different approaches (memorialization, gacaca courts) aimed both to remember and to provide local forms of justice. These divergent models show the range of ethical trade-offs societies make when balancing reconciliation, deterrence, and collective trauma.

A Practical Decision Checklist

- Identify the specific memory/record.

- Map stakeholders (victims, perpetrators, community, future generations).

- Assess harms and benefits across psychological, social, and civic domains.

- Verify accountability and restitution steps taken.

- Seek consent and give voice to affected parties.

- Consider public interest and historical record.

- Evaluate reversibility and technical limits.

- Decide transparently and document reasons.

Step-by-step guide for institutions:

- Convene a multi-disciplinary panel (legal, ethical, victim representatives, technical experts).

- Conduct a harms audit: identify direct and indirect harms of retention vs deletion.

- Solicit public comment and prioritize perspectives of those most affected.

- Draft a remediation plan (redaction, restricted access, contextualization, or deletion) with timelines.

- Implement with oversight and offer appeals processes.

- Publish rationale and review decisions periodically.

These steps make the ethics of forgetting operational and defensible.

Expert Perspectives and Quotes

- “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” wrote George Santayana — a caution that memory supports collective learning. But as policy analyst Aleida Assmann and others note, memory must be balanced with the needs of survivors.

- Legal scholars interpreting GDPR emphasize that the right to erasure is not absolute; it must be weighed against free expression and historical memory.

- Clinicians emphasize that ethical therapeutic practice centers consent and realistic outcomes: reduced distress, not miraculous erasure.

Including expert voices helps anchor decisions in disciplinary knowledge while keeping the experience of affected persons central.

Comparative Analysis: Cultures of Remembering and Forgetting

Different societies institutionalize forgetting in different ways. Post-authoritarian societies often face a choice: public trials, truth commissions, or negotiated silence. Democracies may choose to archive painful records while protecting individuals’ privacy through access controls.

A comparative look:

- Spain: pact of forgetting after civil war — stability prioritized, later debates reopened wounds.

- South Africa: TRC — public truth and conditional amnesty; emphasized restorative practices.

- Germany: vigorous memorialization and legal accountability for Nazi crimes supports collective remembrance.

The ethics of forgetting is shaped by history, power, and the political aims of each society.

Future Trends and Predictions

- AI and Big Data will complicate forgetting: automated profiling and deep archives make personal erasure harder and easier to circumvent. Expect legal regimes to expand beyond GDPR-style erasure toward algorithmic transparency and data minimization.

- Biotechnology and memory-modulating drugs (still experimental) will raise new questions about consent, identity, and the limits of therapeutic forgetting.

- Social movements will push for more victim-centered redaction policies in archives and media, while historians will advocate for accessible context and non-destructive methods (e.g., restricted layers of metadata rather than wholesale deletion).

- Platform design may shift toward ephemeral architectures and stronger user controls over personal data lifecycles, aligning technical possibilities with the ethics of forgetting.

Closing reflection — forgetting as moral practice

The ethics of forgetting asks us to balance compassion with accountability. Letting go can be merciful and necessary, but never lightly used to conceal wrongdoing. When in doubt, favor structured or reversible approaches: redaction, contextualization, or time-limited silence that preserve truth while protecting dignity.

Which memory asks you to release it, and why? Reflect, consult affected voices, and choose with care.

References & Further Reading

- GDPR (EU Regulation 2016/679) — Article 17: Right to Erasure.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy — Forgetting and Memory.

- Selected neuroscience reviews on memory suppression and trauma (see NCBI/PMC articles for research summaries).

(If you are dealing with trauma consult licensed mental health professionals; for legal data-deletion questions consult privacy counsel.)